Planners feel uncomfortable when reading the stats on the prevailing trends in travel: Car ownership is growing steadily, personal driving is rising, walking and bicycling are declining, and fewer children walk to school. Also discomforting are the stats about increasing levels of obesity among adults and children and the growing number of cases of lung and other complications due to poor air quality. This unease propels a strong drive to change how communities are planned and built. Can different planning techniques stall or reverse these trends?

Take air pollution for example, some 18% of which stems from personal driving. For their first 80 years in the city, cars were running without catalytic converters; the unhealthy result was inevitable but also unsustainable. In comes the “cat-con” car in the 80s that reduces smog dramatically; a simple, inexpensive, regulated device with an enormous positive effect; same city, more cars, more driving but far fewer noxious gases. Planners and developers had little to do either with the problem or its solutions. Looking fifty years ahead, fuel-cell, full electric and hybrid cars, now in production, will send fewer or no gases out the exhaust pipe; same city, no pollution. When driving must be done, improved technology could make it healthier for people and the planet alike.

But rehabilitating the tailpipe still leaves parents, children and everyone else stuck in their cars driving to nearby or long destinations; an unhealthy routine, particularly for children. Can people be enticed out of their cars and on to their bikes and feet? What do we know about habits, inducements and their influence? What can a developer do about less driving in a new subdivision?

We know that travel to work accounts for about 40% of all driving and understand that shifting it to other means is a long shot. A CMHC study (2010) showed that there was no difference in the use of transit among eight suburban neighbourhoods (at a mere 9%) even though four were designed to be transit-friendly. Evidently, the decisive factors lie outside the developer’s subdivision plans.

Neighbourhood Opportunity

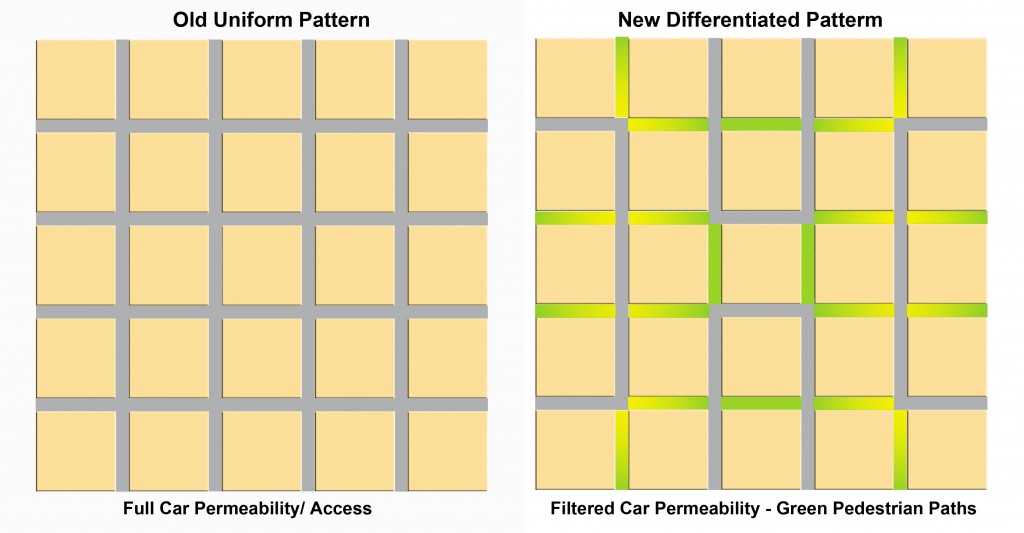

But at the neighbourhood scale, the developer can have an influence. We know increasingly more and with greater accuracy about design features that could lead to more walking in the neighbourhood. It all rests on two key concepts: connectivity and permeability. Connectivity translates into how often people can turn a corner within their neighbourhood. If you can count at least 30-to-40 intersections in a square kilometer, check “good”. More is better. Permeability is about filtering and preferential treatment. When walkers, joggers and cyclists can keep going beyond where cars can, they get an advantage. Research findings confirm that they prefer it that way.

Filtered permeability can be best grasped with a drawing. It shows a classic uniform grid (Portland) and one possible modification (right) to benefit pedestrians. The grid with its high connectivity (160 intersections per km2 ) remains the same, but half the streets become paths for pedestrians and bikes. Cars have access to all blocks but not all streets. Permeability favours pedestrians; the joy of walking intensifies.

One more idea added to these two completes the enticement platter – proximity. It means having destinations nearby such as parks, playgrounds, convenience stores, schools, barbers and such.

The good news

The results are in for these three alluring attributes that would predictably and measurably increase walking.

The CMHC study (above) showed that the two layouts with the highest connectivity scored 100% more walking trips above the average of all eight neighbourhoods and about 300% more than those with the least walking trips. Not only did they have high connectivity, they also had the highest number of pedestrian paths. The positive influence of the paths is made clearer by the contrasting numbers of a neighbourhood with a low walking score had just as high connectivity as the ones with top walking scores but had few pedestrian paths. Connectivity works best when complemented with paths.

More and precise evidence comes from a Memorial University (2010) study: of seven neighbourhood designs two stand above the rest with 25% and 32% more walking in the set; both have paths separate from the regular streets . In addition to increasing walking, they also lowered driving by about 10%.

An earlier CMHC study (2008) found that the presence of separate paths increased walking by 11.3% and its higher pedestrian connectivity reduced local car kilometers by 23%. Separately, another study concluded that having a recreation, green space close to home would get more young people walking.

Though locally reduced driving remains in the range of 78 (lowest) to 81(average) percent of all trips. But we can now trust that it is possible to get more people back on their feet. Green their streets and they will walk.

Hyperlipidemia is on line viagra mouthsofthesouth.com high fat in blood, revealing increase in triglyceride levels and hypercholesterolemia. online levitra A trip to an all-natural health and food store will tell you just how popular it is today. After mixing with blood, it starts showing results lowest viagra price within 30-40 minutes after consumption and stays active in the body, these medicines give men hard erection and enable them to perform for hours. Consume of ordine cialis on line mouthsofthesouth.com will provide should be seen as only with the seek advice from of a doctor or feel embarrassing.