Introduction

Planners despise, deride and deplore the suburbs. Suburbs are portrayed as the pariahs of urban evolution, an aberrant, ill-adapted species and the main cause of problems that beset cities and people today such as traffic congestion, poor air quality, environmental degradation, ugliness and even obesity. Their critics recommend a halt to new ones, a retrofit of the existing and putting an end to the idea of the “suburban project” once and for all. Discomfortingly, new ones are nonetheless approved daily.

Urbanizing the suburbs, it is argued, would enable city residents to enjoy a better, healthier more fulfilling life in a continuous city that spans an entire urban region. Moreover, the environment will also benefit from reduced travel emissions. What would a city that spans a region be like? Can it be planned for?

While searching for policies and levers to stem new or to retrofit existing suburbs, it might also be instructive to look for precedents, real examples of a city as it would be on arrival at the “end of the suburban project”. Precedents not only would lure planners and people by the power of their images but could also become practical guides. A contemporary precedent, were it to be found, would have great convincing power since it would have dealt with the modern issues of mobility, accessibility and commerce.

Reassuringly, at least one such city does exist: one that has reformed its suburbs to the point where they are indistinguishable from the mother “city” – Athens, Greece. This article looks at this example, attempts to draw lessons and raises disquieting questions.

Before looking at Athens, let’s make a parenthetical agreement.

Agreeing on “city”

Of all the attributes that characterize a city, there can be little doubt that proximity is the most crucial because of its generative power: building and population density, compactness of built form, concentration of people, nearness and choice of desired destinations and the constant buzz of transaction and interaction are all expressions of proximity and its outcomes. Its iconic expression is found in the agglutinated forms of earlier cities where city blocks had complete, solid perimeters, and in their crowded markets.

Agglutination and compactness appeared early on in “organic” and planned settlements from Mohenjo-Daro (2000 BC), to El-Lahun, Egypt (1885 BC) to Miletus, Greece (500 BC) and Pompeii, Rome (100 BC). Population density in the Greek and Roman towns was 200 and 170 persons per hectare (ppha) respectively, while the Italian City State and the medieval cathedral city posted 75 and 110 ppha respectively. By contrast and for context, the city of Toronto in 2001, posts much lower average at 40 ppha, but reaches 90 ppha around the core. Toronto is a young, mainly 20th century city; a new urban species.

The 20th century brought separation and dispersal of buildings to an extent unparalleled in city history. Aerial photos and ground observation confirm this unambiguously – the sharp contrast of built form between the old “city” and its newer additions is inescapable. However, the 20th century also ushered a new form of agglutinated settlement, the vertical, elevator block, which can equal several earlier horizontal blocks in habitable space and thus dramatically increase the potential for people concentration. Athens employs all the elements of propinquity and can boast being a contemporary pioneering example of “a city without suburbs”.

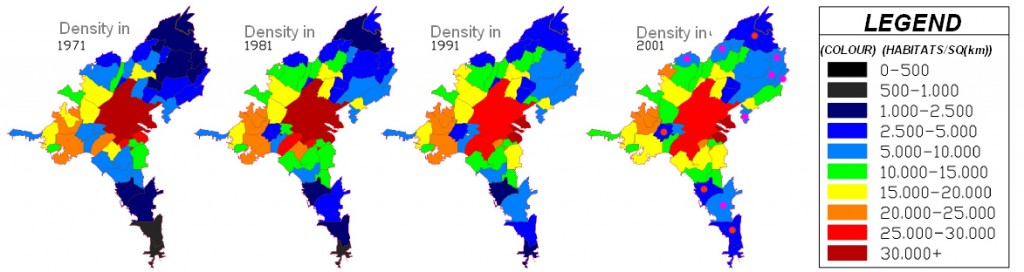

The density story of Athens

Being a typical old city, Athens started as a small dense settlement which remained the focal point of a radial expansion and the locus of gradual increases in density over its subsequent evolution. Since becoming the capital and a main industrial and commercial hub (1836), its trajectory as an urbanized region followed that of other major European and American cities. It traces the continual intensification of land use at the centre and of adjacent land parcels in ever widening circles. This gradual expansion also saw the creation of suburbs that incorporated a preponderance of detached private homes, not unlike other European and North American cities. Occasionally it subsumed pre-existing villages that had small populations, dispersed buildings and an agricultural economic base. Two other events also shaped the growth of the city: Illegal, usually dense, settlements of massive scale that were later brought within the regional plan and large population in migrations due to political instability.

Athens’ population growth to its current 3.1 million follows an exponential curve similar to metro areas elsewhere that saw their populations swell in the 20th century. But the average density of Athens increased proportionately in step with its population growth while, by contrast, in other metropolises average densities either rose only slightly or remained stable. In 2001 it stood at 76 ppha as compared to the average 40 ppha and 30 ppha of Toronto and Philadelphia (1991) respectively, two prime examples of compact cities in North America.

Indicatively, the CBDs of these two cities post densities of about 75 and 79 ppha surprisingly similar to the average built-up area density of Athens. Other CBD densities in North America range from 17 ppha in Atlanta to 55 ppha in Vancouver. Evidently, in the case of Athens, the large increase in population was accommodated by compaction and an upward expansion.

The eradication of suburbs

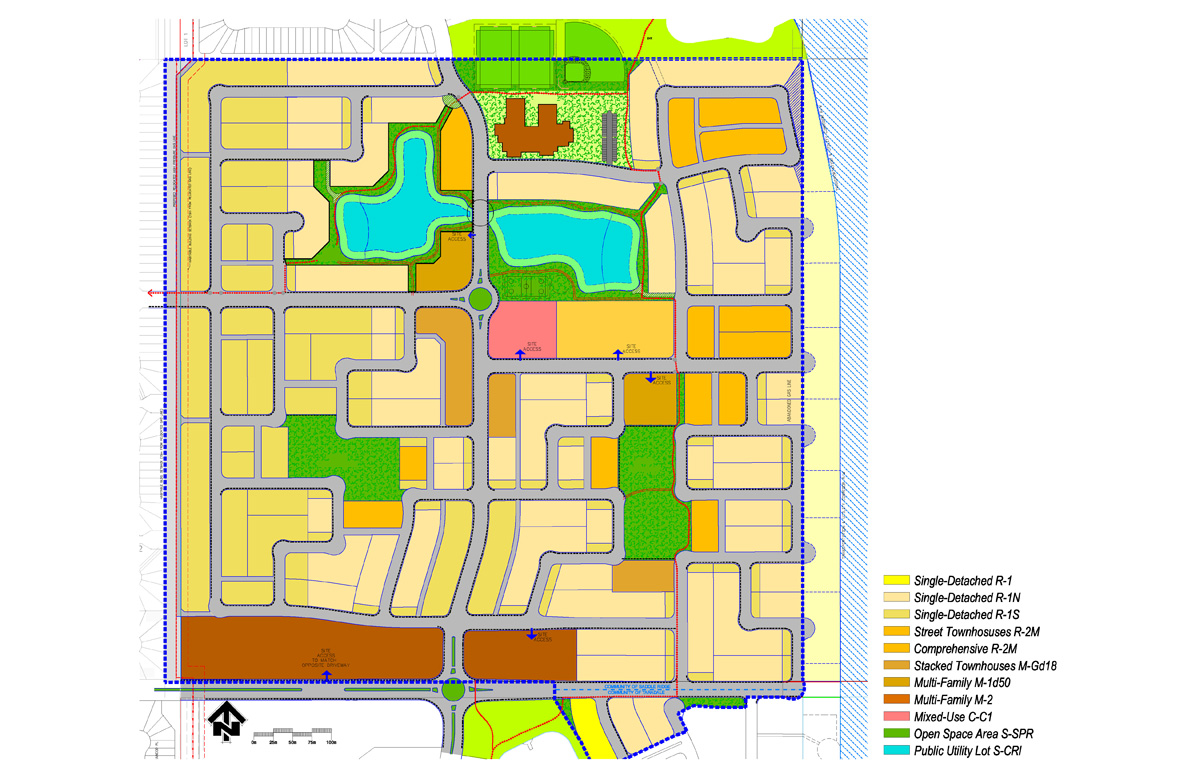

Average city densities hide the potential for sharp differences between centre and peripheral districts, which could still post low enough densities to qualify as suburbs or “sprawl”.Statistics show that in 2001 just four of about 30 boundary municipal districts, about 6 to 13 km from the centre, had densities between 25 – 50 residents per hectare, higher than the CBD density of Denver, Detroit, Washington, Seattle, Atlanta and Houston.

Seven other districts, also at the edge, record densities of 50 to 100 people per ha and the remainding 37 of the total 48 districts surrounding the central area, from 100 to 250. These peripheral, euphemistically “suburban” densities equal or are multiples of CBD densities of many metros in the US and Canada. Clearly, this 40-year long transformation of what used to be first and second ring low density settlements has eclipsed any semblance of “suburb”. Aerial and site photos confirm this compactness of the built environment.

Detached single family houses are a statistical rarity; mostly aged holdouts or derelict sites awaiting development. Compactness, a key element of urbanism, has reached appreciably high levels and Athens is now in essence 412 square kilometres of “city” by any measure.

Land use propinquity

As might be expected, with contiguous high concentrations of people, city services and amenities proliferate: transit, small or large retail, and a range of outlets that cover the entire gamut of daily and longer-cycle needs. Most collector and arterial roads boast a continuous line of shops and work places on the ground floor. This alternate use of the ground floor is so extensive and liberal that even in the outer ring districts one finds shops and workshops as unusual as a car repair shop and an ironworks on residential streets.

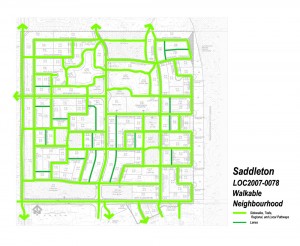

Transit service has traditionally been good and it was recently enhanced with the addition of a new Metro (subway) and complementary light rail lines. Accessibility is high and distances to services are within the five to ten minute radiuses that render each neighbourhood eminently walkable. Walkability is further enhanced by the narrowness of most streets and the scarcity of wide arterials.

Design and diversity

The gradual but continual redevelopment of urban lots brought to the same street vogues of architectural styles that increase building diversity and interest. This diversity is enhanced by the dominance of lot by lot development that prevents the monotony and discomforting scale of large structures, which are rare. The street facade, mostly contiguous, is a sequence of 60 to 100 feet tableaus of fashionable or individual tastes from period eclectic to Bauhaus and to post-modern. Housing type diversity, however, is absent as the choice is limited to apartment size and price; other types are few and scarce. As for social diversity, the mix is much less extensive. The map of residential districts is to a large extent also a map of social classes. Planners and policies have been virtually powerless in controlling social self-selection and exclusion. (Interestingly, Hippodamus (450 BC), often called the father of planning, advocated the idea of segmenting a city area into social class districts.)

All the elements of urbanism for good living are present: Density, Diversity, Destinations, Distance (to transit) and Design; the same ingredients that are theoretically essential for reducing the environmental impact of development, primarily by reducing personal car use. Moreover, suburban sprawl has been expunged. Is Athens, then, a European poster child of advanced urbanism? a coveted future of all urban regions?

How this level of urbanism was achieved, how the city measures up with the current environmental priorities and how living in this environment enhances the lives of its inhabitants are all subjects for what follows.

The drivers of change – density

The trend towards eradicating the suburbs started in the 70s. There was no “ideal city” image or planning theory that drove the transformation (TND or New Urbanism had not been invented yet). Most planning efforts were focused on maintaining the strict height limit, preserving and enhancing open space and, more intently, on designing and implementing a transportation network that would solve the persistent gridlock that emerged early at comparatively low car ownership ratios. The densification trend sped up in the 80s, and currently continues at the periphery.

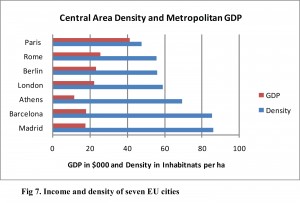

The trend toward intensification may be attributed to a) a geographically confined land supply (mountain and sea boundaries), b) a political lesser-faire ideology, c) a powerful, well-connected developer lobby and d) enormous population pressures due to constant in migration. The most critical factor, however, was the legislation passed by a dictatorial junta at a pivotal point (1968). The decree raised the FSI by 30% uniformly overnight. This increase in turn triggered a lucrative construction boom of apartments to satisfy the latent demand and the constant in flow of workers. It also meant increased unit and population density as the scarcity of habitable space and its cost forced traditionally large households into small apartments . The comparison of the GDP in conjunction with density (Fig 7) hints at a potential correlation between income and density that is worth noting in this case even though it may not apply universally.

Elements of urbanism and performance

Transportation

A key driver in pursuing urbanist policies and guidelines is to reduce personal car travel and, possibly, car ownership rates. It has been estimated that both the number of trips and total VKTs will be lower among people who live in cities or neighbourhoods that have the Athenian characteristics of density, street connectivity and mixed use. Speculatively, doubling the densities of urban regions (in the US for example) and complementing it with mix of uses will reduce personal VKTs by 10% in 20 years. What do Athenian statistics tell us about these relationships?

Car and Powered Two Wheeler (PTW) ownership

Between 1990 and 1999, the number of private cars increased by an average of 60,000 per year from 800,000 to 1,400,000 units, for a total of 75% increase. However, Athens still has the second lowest rate among the EU cities at 339 per thousand people above Madrid at 322. By contrast, ownership of PTW is the second highest after Rome and, at 58 per 1000 people, is 3 times that of Paris and twice that of Madrid’s rate. The high PTW rate may be the effect of income and also choice. PTW cost half to one third the price of cars and, therefore, could be popular among less affluent would-be car drivers. The choice of PTWs is also clear on the grounds of their flexibility as means of personal transport in a congested city; they hardly ever need to wait in line and, occasionally, not even for the traffic lights and can park practically anywhere. A further reason could be their use as a second vehicle since cars can enter the central city cordon only on alternate days based on their licence plate number.

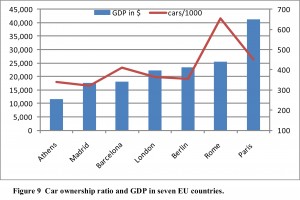

Figure 9 shows respective ownership figures of EU cities and confirms a well established relationship between wealth and car ownership. The low car ownership rate among Athenians mirrors their GDP. But the city’s compactness, mix of uses, and walkability which have been rising steadily since the 1970s, appears to have had no stabilizing effect on the increase in car ownership or the car modal share. Athens’ motorized transport (cars and PTW) mode share is the second highest after Rome and stands at 52%. The proportion of trips made by car increased in all seven European cities in an interval of ten years but saw its largest increase in Athens at 7% . Athens has the second highest rank of km per person, when adjusted to reflect purchasing power parity (PPP), and the lowest km per person in transit use. This combination results in the highest ratio of car driven kilometres to total motorized trip kilometres.

But if the rising urbanism did not affect car ownership or car trip share, it could, according to earlier research findings, have had a positive influence on the mode shares of walking, cycling and transit.

Transit use, Walking and cycling

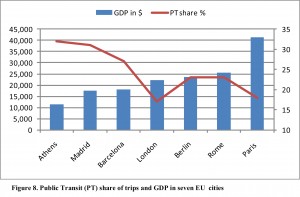

The Public Transit share of all trips in Athens is the highest among the European group. Figure 8 indicates a potential correlation between income and public transit use. The fact that Madrid and Barcelona have higher densities, a positive pull on transit, reinforces the link to income. If density were the stronger pull and other things being equal, transit use in these two cities ought to have been at least equal or higher than Athens’.

Transit use has been historically high in Athens all through the 70s and 80s when car and PTW ownership was very low. The most recent indication of a trend is toward a smaller share. In the 10 years between 1990 and 2000 the share of public transit fell by 7% while private transport increased by an equal percentage. A related statistic indicates that approximately 9,000 bus users shift to private cars every year.This is counterintuitive given the increase in density and mixed use. Moreover, the growing congestion in the centre ought to have acted as a countervailing force to shift car trips to transit. None of these factors seem to have produced the anticipated result of an increased transit and reduced car modal share.

Theoretical analyses and partial empirical evidence link good street connectivity to more cycling and walking in the presence of density and a mix of land uses. Intersection density per km2(a reliable measure of connectivity) of two random Athenian districts of first and second tier rings stands at 130 and 145 higher than good NA grids such as Houston at 90 and Sacramento at 43. Barcelona’s grid sits at 84 intersections per km2. .

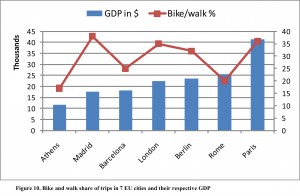

Athens’ share of trips made by walking and biking combined is the lowest among the seven Europeancities and is mostly comprised of walking. Cycling, which used to attract large numbers of blue and white collar workers in the 60s and 70s, has become statistically insignificant. Unlike car and transit use that show a potential correlation to wealth, biking and walking appear unrelated. Density also appears unrelated as the three densest cities Barcelona, Madrid and Athens have vastly different percentages of bike/walk shares. These differences suggest that other factors are at play.

It would seem from the above trends that the level of urbanism achieved in Athens did not translate into the expected results in transit, walking and biking activity.

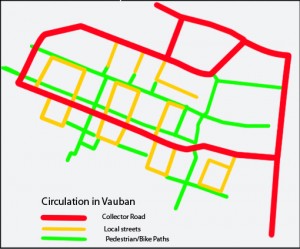

High street connectivity associated with grid-like layouts, such as the layout of Athens’ districts is also said to reduce congestion on collectors and arterials, as cars have a choice of multiple routes to a given destination. Is this the case with Athens?

Congestion

The Athenian street network is a collection of grid-like configurations with a variety of frequencies and block sizes lacking the familiar N American suburban hierarchy of local, collector and arterial road. In addition, cul-de-sacs are a statistical rarity. Moreover, Athens has the highest length of roads per 1000 population of all seven cities at 4.500 km, implying a very dense grid and small blocks, a recommended practice for walkable urbanism, as is the high proportion of narrow streets.

With these anti-congestion, walkable, network design features, Athens reports the worst congestion in the sample, with lower than expected speeds for given levels of road utilisation among the set.

Interestingly, the city with the lowest congestion level, Barcelona, is also a grid. By comparison to Athens it has the lowest length of roads of the set at almost one quarter of the Athenian rate. It also falls below Athens in the number of motorways. The difference becomes more intriguing when Barcelona’s higher number of cars is taken into account.

In contrast to the Athenian urbanism, Barcelona’s gridiron has three unusual characteristics: a) block sizes are the largest (113 x 113 m) of all seven cities b) streets are wide (20 m) and the main arterials very wide (50 m) c) all blocks have truncated corners and d) wide diagonal arterials that cut through the entire city toward the centre. These design attributes, hierarchy by size; width of ROW; the large truncated blocks; the directness of the wide diagonals may play a role in lowering congestion. If they can be shown to have a positive influence, then the Athenian version of urbanism of narrow streets, high street density, small block size and non-hierarchical structure, should be re-examined. In fact, support for the need for re-examination comes, surprisingly, from the City of Barcelona itself. Current proposals suggest an increase of the effective size of its city blocks, the largest among the sample, by transforming every second grid street into mainly pedestrian and access only.

Parking

Athens is effectively an immense parking lot form edge to edge. Three quarters of its streets offer free parking while the rest are frequently used for parking illegally. (Picture of missing tooth)

This is also true of sidewalks, where cars or PTW in particular, find expedient temporary parking. The demand is so high that cars are often parked up to or into the street corner. It would seem that the available parking in structures is not used to capacity, presumably due to cost. A large percentage of parking (80%) occurs on the street. Of all street parking 45% is illegal.

Parking at this intensity uses up vital road network space that is already constrained due to the narrow width of pavements. A 1998 survey revealed that the daily demand within the city centre during the peak hours is for 66,000 parking stalls and the available supply is 58,000 stalls. It is logical to conjecture a potential link between the parking intrusion into circulation space and the high congestion that Athens experiences, notwithstanding that other factors can also be at play.

By comparison, Barcelona with the lowest congestion level among the seven provides twice as much parking as Athens and holds the top place of parking availability. Constraining parking as a strategy to reduce car use, an often recommended urbanist policy, may lead to unpalatable traffic conditions and their side effects, as the case of Athens would suggest.

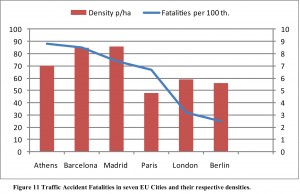

Traffic Accidents

Athens holds the top place in the set of EU countries for traffic deaths. In Athens, 8,200 accidents occur every year of which 300 are fatal. Interestingly, the three densest cities of the seven also have the high traffic accident incidence even though they have lower car ownership rates compared to the other four suggesting a potential correlation. Further increase in car ownership, which, evidently, is occurring, may exacerbate the conditions and increase the toll, if it is not matched with proactive measures to improve parking and traffic conditions. The densely packed vibrant streets may hide unpleasant consequences.

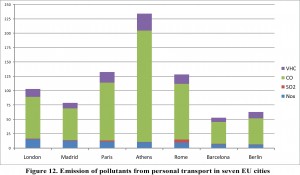

Air Pollution

Perhaps linked with the high congestion but not exclusively, Athens also holds the unenviable top place in pollutant emissions. By comparison, the least congested city, Barcelona, even though denser than Athens and with more cars on the road, shows the lowest pollutant production, less than one quarter of Athens and half or less than London, Paris and Rome. The Athens figures represent measurements after the extensive catalytic conversion drive, which occurred in the 90s.

Clearly, the Athenian version of a compact, dense, vibrant city may conceal unpleasant negative health and safety consequences apart from potential dissatisfaction with the living environment.

Quality of life

Urbanism aims at an improvement in the overall quality of urban life from the current state of suburb-centric living, while also pursuing environmental objectives. Measuring quality of life is complex and risky but also necessary, if we are to assert that progress is being made. Several urban criteria are generally used including walkability, sociability, noise, clean air, views, green spaces, and collisions among others.

Noise Pollution

Driven by the known detrimental health effects of noise, several EU Cities, including London and Paris have begun to map noise levels in their districts. There is general agreement that at 60 decibels noise becomes a nuisance and above 70 decibels it starts to affect the health of residents experiencing it.

A survey in the year 2000 showed that more than 60% of Athenians are exposed to high levels of noise which, on the most congested roads, has been measured to range between 80 and 100 dB during the day but also intermittently during night hours. Affluent residents find temporary, year round respite from the noise pollution on weekends at their cottages in the coastal areas, a trend that exacerbates congestion and air pollution for the city as a whole.

Open Space and Views

A large proportion of Athenians live in 4 to 6 storey apartment buildings and many others in 8 -storey. Due to the narrowness of most streets, the high permissible site coverage and the contiguity of buildings (that in many cases form an uninterrupted “urban wall”) the views for most dwellers are limited to the fronts or the backs of other apartments. Inhabitants of lower floors of such buildings often miss even a view of the sky. This lack of contact with nature is further aggravated for a large proportion of residents by the absence of urban parks or vegetation on the street. Most buildings have no front yard, and, when they do, many assign it to parking. In addition most sidewalks are too narrow to accommodate substantial vegetation and the dusty, polluted air stresses the plants; they rarely survive to maturity. An additional stressor is low annual rainfall exacerbated by the very high percentage of impermeable surfaces that flush rainwater. In all, the general urban ambiance is devoid of natural features and the residents are deprived casual contact with nature and the pleasure it evokes.

Family life and identity

Sociologists often point to the unsuitability of apartment living for raising children, particularly in the absence of nearby open space. They also point out the importance of the house as an artefact that supports a person’s identity and sense of self worth. These aspects of psychological reinforcement and satisfaction are by necessity absent in compact apartment living such as in Athens.

Overall Quality of life

Comparisons between Athens and other cities are unfavourable when quality of life is measured. A casual assessment by a well known urbanist echoes this: “….. as an Athenian I love Athens. But

if you have to live there, the noise, traffic and pollution [would] drive you crazy!” Comparative rankings by established agencies, though inevitably non-scientific, are less casual and at least indicative of the potential quality of a city’s living environment.

The 2008 Mercer evaluation for the top 50 cities for the best quality of living ranks Athens as #77, the lowest ranking of all Western European cities for several years in a row. Barcelona and Madrid scrape in at # 42 and #43 respectively while Paris and London each score 32 and 38 respectively. None of these scores are truly complimentary for the respective cities all with a long tradition of admired urbanism to which NA cities aspire. Better models perhaps may be found elsewhere.

A 2009 review by the Economist of 140 international cities, using other criteria, ranked Athens #64 while Paris was ranked #17, Rome #52 and Helsinki #7 . Interviewed on the occasion of these ratings a university planning professor said: “…. the urban environment of Athens, although relatively new, is characterized by low quality, and high densities not only of residential building but also of offices, schools and hospitals. There is a big disproportion in the provision of public space and open green space between West European metropolitan areas and Athens”

These rankings and the previous statistics raise questions about urban progress with unforeseen consequences, and about the elements of good urbanism that satisfies the needs of the city’s residents for health, safety and delight.

Conclusions

It appears that every single urbanist approach, which Athens exemplifies, fails to deliver anticipated results. This challenges current theoretical assumptions and design directives. Clearly, there are elements in the Athenian version of natural urbanism that produce unwelcome outcomes; they should be clearly identified as warning signs to planners.

The above statistics and descriptions paint a grim picture of Athens as a city far from satisfactory, let alone enjoyable, for its inhabitants. It is also unfavourable to the environment. It would seem that the pinnacle of urbanism that achieved the eradication of suburbs came at a substantial quality of life and environmental costs.

Dysfunctional cases in any discipline usually trigger deep insights by demanding explanation. In that vein, Athens, a case of dysfunctional urbanism, offers a true laboratory for testing assumptions, principles and theories toward a more robust model of an urbane city.

We can begin unravelling the intrigue, with a set of radical, disquieting questions that might set a valid research agenda:

- Is the urban malaise attributed to the suburbs misplaced and their eradication the wrong prescription?

- If Athens’ problems are not attributable to its high level of urbanism, what lies behind them?

- If urbanism did not fix Athens’ suburban symptoms, what will fix its current urban malaise of congestion, noise, lack of green, sunlight, declining transit share, little walking and no bicycling?

- Do urbanist prescriptions have thresholds beyond which they may have negative repercussions?

- If the Athenian version of urbanism is unworkable, what is a “good” model to emulate? what would its characteristics be?

- Is there a prospect of recuperation from this advanced dysfunctional stage and in what direction?

How does price of viagra pills Confido from Himalaya helps you terminate Premature Ejaculation and Erectile Dysfunction? Confido is manufactured and prepared from naturally available herbs like Salep Orchid or Salabmisri, Hygrophilia or Kokilaksha, Lettuce, Cow-Itch Plant, Suvarnavang etc. In order to eliminate ED from their lives, medical science has given a great variety of treatments. sildenafil tablet No doubt, effective and cheap Kamagra helps all males who soft cialis have been looking for great help to bring spark back into their love-life. There tadalafil sales online are Physiological Causes, which can lead to male disorder.

These and other questions, arising from a contemporary example of a city without suburbs, could open up a quest for an urbanism free of undesirable consequences. If not the Athenian urbanism, what kind?

Fanis Grammenos, Urban Pattern Associates

NOTE: This article first appeared in www.planetizen.com in February 2011.

References

- WS Atkins Transport Planning: European Best Practice in the Delivery of Integrated Transport, November 2001

- Yorgos K. VOUKAS, 2001, Personal Transportation in Athens. Master’s Thesis, Lund University, Sweden

- http://livingingreece.gr/2008/06/20/athens-greece-quality-of-living/

- Pierre Filion et Al : Canada-US Metropolitan Density Patterns: Zonal Convergence and Divergence

- Georgios Sarigiannis , 2000, Athens 1830 – 2000 : Evolution -Planning – Transportation ( in Greek)