The rise of women’s role in society: impacts on housing and communities

Author: Luis Rodriguez

The rise of women’s role in society will result in significant impacts on housing and communities across Canada, not too far into the future. With their rapidly rising economic power and highly heterogeneous nature, lifestyles and housing needs and preferences, women will not only be influencing future housing demand, but also defining the types of communities and housing in which they will want to live in, says planning consultant Luis Rodriguez

—————————————————————————————————————–

—————————————————————————————————————–

In the coming years, a number of emerging demographic and socio-economic trends will shape our housing and communities —neighbourhoods, villages, towns and cities. These trends indicate that families are getting smaller and the structure of the Canadian family is changing; the numbers of immigrants and visible minorities are growing; life expectancy for Canadians is increasing; the bridges between generations are expanding; young adults are tending to remain in, or return to, their parental home depending primarily on the state of the economy; more Canadians are living alone than ever before; the Canadian population is aging rapidly; real household incomes and retirement trends are changing; urban dynamics are shifting; and women’s role in society is on the rise. There is no doubt that each of these trends will accelerate rapidly in the coming years and that they will start having significant impacts on housing and communities not too far into the future.

This article examines the rise of women’s role in society and its potential impacts both on housing and communities. It shows that women have significant impacts on the housing markets in all major cities across Canada —and on the way communities are planned and designed— and that these impacts will only be increasingly stronger as we move into the future. The article also suggests that now is the time for community policy makers, planners, designers, developers, and the housing industry in general, to start tapping into women’s unique housing and community needs and preferences.

When did it all start and what is happening?

In the early part of the 20th century, the primary role of most adult women was to care for their family and home. By comparison, men more often worked outside the home for pay and assumed the role of the household head.[1] As an example, in 1911, only 7.8% of the household heads were women.1, [2]

However, and particularly over the past sixty years, Canadian women have progressively become more important in society and —through this path— have turned the idea of taking leadership in the social, economic, and political fronts into an increasingly balanced responsibility between men and women.

In fact, the Canadian women of the 21st century are more highly educated, more numerous and important in the labour force, more involved and successful as business entrepreneurs and business leaders, more independent and powerful in decisions regarding their housing and their home finances, more influential in politics and, in general, more economically powerful in society. For instance, in 2006, women were the primary household maintainers2 in 38% of the total (owners +renters) private households in Canada;[3] and in 2010, women in dual-earner couples born from 1981 to 1990 did 47% of couples’ total paid work and 53% of couples’ housework.[4]

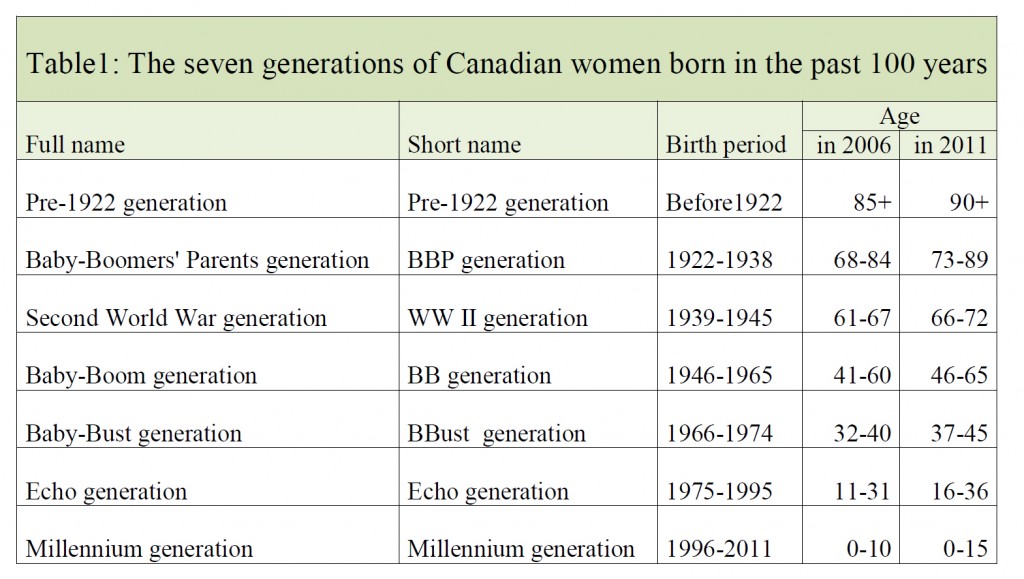

Women’s impacts on housing — one generation at a time

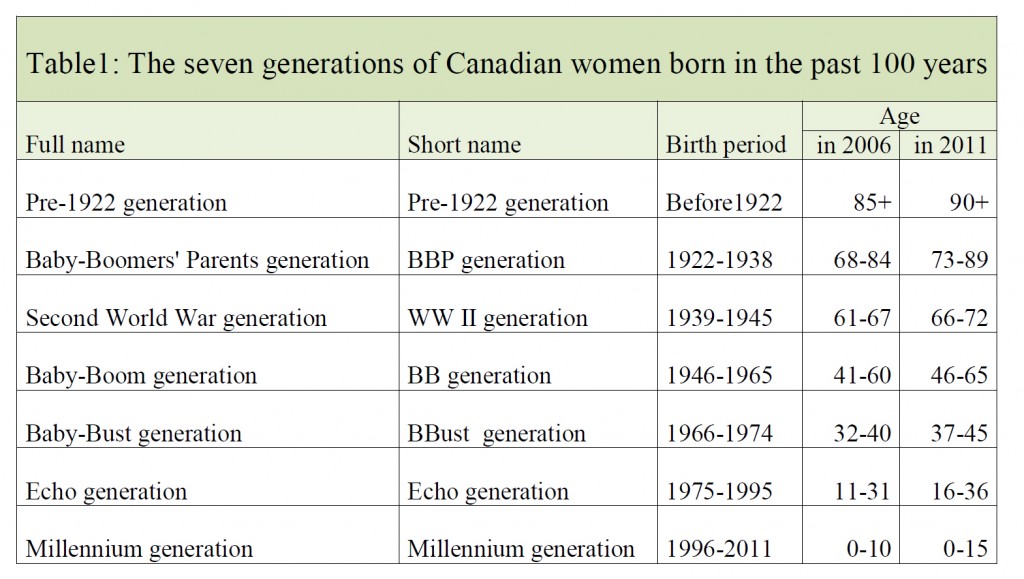

There is indication that women have significant impacts on the housing markets in all major cities across Canada. A 2007 Royale LePage survey lends credence to the trend, illustrating, for example, that women drove a large portion of the activity in the condominium market in Halifax; home buying among women increased significantly in Montreal; and first-time women homebuyers represented the most active purchasing group in Vancouver.[5] It is also very apparent that women’s impact on housing and communities will only be increasingly stronger as we move into the future. Let us take a brief look at six of the seven generations of Canadian women born over the past 100 years (Table 1) to see what might happen. The seventh generation —the Millennium Generation— will not be included in these discussions because the girls of this generation, who will be only between 0 and 15 years old by the end of 2011, are too young to qualify as primary household maintainers.

Table 1 —Source: Statistics Canada. 2007. “Portrait of the Canadian Population in 2006, by Age and Sex, 2006 Census. Age and sex, 2006 Census. Census year 2006.” Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 97-551-XIE. July 2007. Page 13. Retrieved on 13 February 2011, from: http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/english/census06/analysis/agesex/pdf/97-551-XIE2006001.pdf

The women of the Pre-1922 Generation — born before 1922

The women of the Pre-1922 Generation make up most of the current “very old seniors” group of the Canadian population. They had the largest number of children of the women of all the generations discussed in this article and, therefore, they have been able to rely on them for much of their support needs and companionship.

Of Canada’s 172,100 private households in which women of the Pre-1922 Generation were the primary household maintainers in 2006, roughly 52% owned their home and 48% rented it. Of the households that owned their home, 67% lived in single-detached houses, 20% in apartment buildings and 13% in other dwellings, such as semi-detached houses, row houses, flats in duplex apartments, mobile homes and other single-attached houses.

In spite of their advanced age, it is possible that most of these women will still wish to continue to remain in their current home for as long as possible —even if there were increasingly significant changes in their health or living arrangements. As a result, there will be a growing demand for home modifications, new technologies, assistive devices, and a range of personal, home and community support services designed to help them remain independent in their home.

Those who may not be able to remain in their current homes any longer will most likely prompt a demand for alternative forms of accommodation, such as supportive housing and assisted living.

It is, therefore, very apparent that over the next decade or so, Canada’s housing and support service industries will be increasingly challenged and given the opportunity to find innovative ways of addressing the rapidly changing needs of the women of this generation.

The women of the Baby-Boomers’ Parents Generation — born between 1922 and 1938

The women of the BBP Generation were between 7 and 17 years of age during the Great Depression (1929-1939) and between 17 and 23 years old during the time of the Second World War (1939-1945).

Of Canada’s 815,400 private households in which women of the BBP Generation were the primary household maintainers in 2006, roughly 62% owned their home and 38% rented it. Of the households that owned their home, just over 66% lived in single-detached houses, roughly 18% in apartment buildings and 16% in other dwellings, such as semi-detached houses, row houses, flats in duplex apartments, mobile homes and other single-attached houses.

Whether they live in single-detached houses, apartment buildings or other dwelling — and rent or own their home— BBP women will have two major housing choices: they can stay where they are, or they can move elsewhere.

The decisions of those who decide to stay where they are will most likely result in growing demands for home renovations —such as installing extra handrails along stairs and steps; creating a bedroom, a bathroom or a laundry room on the ground floor of a 2-storey home so that they do not have to climb stairs; or creating a secondary suite that they can rent to others to supplement their income.

The decisions of those who decide to move elsewhere will most likely result in increasing demands for new housing options —such as mingle suites, condominiums and lifestyle retirement communities.

The women of the Second World War Generation — born between 1939-1945

The first-year women of the Second WW Generation were born in 1939. The same year the Second WW started. It was during this War when women’s role in Canadian society started to change dramatically as many women supported the war efforts by working at jobs that were traditionally held by men, and to serve in the military, according to Veterans Affair Canada.[6]

Of Canada’s nearly 387,000 private households in which women of the Second WW Generation were the primary household maintainers in 2006, nearly 66% owned their home and 34% rented it. Of the households that owned their home, just over 66% lived in single-detached houses, nearly 15% in apartment buildings and just over 19% in other dwellings, such as semi-detached houses, row houses, flats in duplex apartments, mobile homes and other single-attached houses.

Increasingly, over the next few years, the women of the Second WW Generation will be reflecting on their current and future housing situation. While reflecting on a range of housing choices for themselves, these women will have a common ground in their considerations: they will be reflecting on the home type, home size, home design, home location, on the amount of home maintenance that is required and on the overall cost of housing. They will also be examining how safe and secure the home and the community in which the home is located are, and on the chances they would have to enjoy a high quality of life.

Therefore, over the coming years, as the women of the Second WW Generation make important housing decisions, they will be prompting a growing demand for a wide range of home renovations and new housing options that can meet their needs and preferences.

The women of the Baby-Boom Generation — born between 1946 and 1965

BB women make up much of the current middle-age population of Canada and are part of a highly heterogeneous population group spanning over nearly 20 years and ranging from women in their mid-forties, who are in the middle or near the peak of their working careers, to women who are entering retirement age (arbitrarily defined as 65 years of age).

Of Canada’s nearly 1,811,300 private households in which BB women were the primary household maintainers in 2006, nearly 67% owned their home and 33% rented it. Of the households that owned their home, just over 69% lived in single-detached houses, nearly 11% in apartment buildings and 20% in other dwellings, such as semi-detached houses, row houses, flats in duplex apartments, mobile homes and other single-attached houses.

Baby boomers have been having an impact on housing and communities since the early 1980’s, when the first baby boomers started to reach age 36. For example, throughout many years as their families were growing, they prompted an incredibly high demand for large single-detached houses in newly developing suburbia across Canada. And it is highly likely that they will continue to have an important impact on housing and communities for the next five decades, that is, until 2060 when they will turn 95. But what will be different at this time is that as BB women grow older, their demands will be switching gradually towards housing and communities that are more supportive of their changing needs regarding their household size, lifestyles and aging. Now that most of their children have left home, BB women’s households are much smaller than they used to be, and BB women have more time for hobbies, recreation and social activities than ever before. In addition, an increasingly number of BB women will be approaching retirement age and facing reality aging from a dramatically closer distance. For these reasons, a rapidly growing number of baby BB women will soon start considering trading their large, suburban single-detached houses for homes that are more manageable, maintenance-free and easier to live-in; and for communities that provide them with better opportunities to capitalize on their free-time, favourite hobbies and desire for increased recreation and socialization.

With their highly heterogeneous nature, lifestyles and housing needs and preferences, BB women will not only be influencing housing demand, but also defining the types of communities and housing in which they will want to live in. Examples of the new types of housing they might be interested in would include housing for the executive women; housing for the work-from-home women; housing for single women who may want to share their housing with others; housing for single women, lone-mothers or widows, who want to live close to family and friends; housing for women in their retirement; and housing for women in the sandwich generation.

The women of the Baby-Bust Generation — born between 1966 and 1974

The women of the BBust Generation are highly educated relative to the previous generations of women and make up an important component of Canada’s current labour force.

Of Canada’s nearly 757,000 private households in which women of the BBust Generation were the primary household maintainers in 2006, just over 59% owned their home, and nearly 41% rented it. Of the households that owned their home, close to 70% lived in single-detached houses, just over 10% in apartment buildings and 20% in other dwellings, such as semi-detached houses, row houses, flats in duplex apartments, mobile homes and other single-attached houses.

Over the past few years, in particular, the women of the BBust Generation have been having important social and economic impacts on communities across Canada through their ongoing activities, such as advancing in their working careers, establishing new social networks, caring for their growing families, participating in recreational and fitness activities, forming new households, and buying or renting new homes. For instance, “from 1997 to 2003, couples in their thirties accounted for the largest proportion (40%) of first-time home buyers, because they were more likely to have formed independent households and there were simply more of them.”[7]

In the future, as BBust women continue to rise in society, we will most likely see an increasing number of them pursuing homeownership. And this, in turn, will most probably result in a steady and gradual demand for new and innovative types of housing and community services.

The women of the Echo Generation — born between 1975 and 1995

The girls and women of the Echo Generation grew up in a knowledge-based era in which innovation in technology and communications revolutionized the way people live, think, create, communicate, entertain, socialize and work. Indeed, this has also been an era in which the world has become more connected and accessible than ever before.

Of Canada’s nearly 766,400 private households in which women of the Echo Generation were the primary household maintainers in 2006, just over 34% owned their home and nearly 66% rented it. Of the households that owned their home, close to 61% lived in single-detached houses, just over 16% in apartment buildings and almost 23% in other dwellings, such as semi-detached houses, row houses, flats in duplex apartments, mobile homes and other single-attached houses.

In 2006, the roughly 4.3 million girls and women of the Echo Generation made up nearly 50% of the total Echo Generation, including men. With this population size, they were nearly 90% the size of the baby-boom women’s population size (4.8 million); they also made up nearly 14% of the Canadian population. Based on these numbers alone, it may not be unreasonable to anticipate that as the women of the Echo Generation move into households of their own, they will at least have as big an impact on housing and communities as their baby boom women counterparts did.

The women of the Echo Generation will most likely be looking for housing that provides them with a sense of safety and security, is affordable, requires little maintenance, and is flexible enough and versatile to meet their unique and changing needs. Many will be looking for housing in which they can live on their own —owning it freehold or in a condominium, or renting it. Others will be looking for housing they can share with their peers — either owning it or co-owning it freehold or in a condominium, or renting it, or co-renting it.

For those sharing a home —which they will probably do either for making their housing more affordable or for satisfying their desire to forming a non-family household, instead of living alone— there will be a need for homes in which all bedrooms in the home have their own private bathroom, storage space and outdoor living area, thus enabling each of the people in the sharing household to have the privacy they need and want. These homes will also need to be designed so that each of the household members, and their visitors, can enter and exit the home and use the common kitchen, washroom, dining and living facilities without interfering with the privacy of the other members of the household.

Over the coming years, the women of the Echo generation will also have increasingly important social and economic impacts on communities through their advancing in educational activities, initiating their working careers, establishing new social networks, participating in entertainment and recreational and fitness activities, forming new households, and buying, renting or sharing new homes. These activities, coupled with their growing desire to succeed in society, will prompt further economic growth and prosperity in communities across the country.

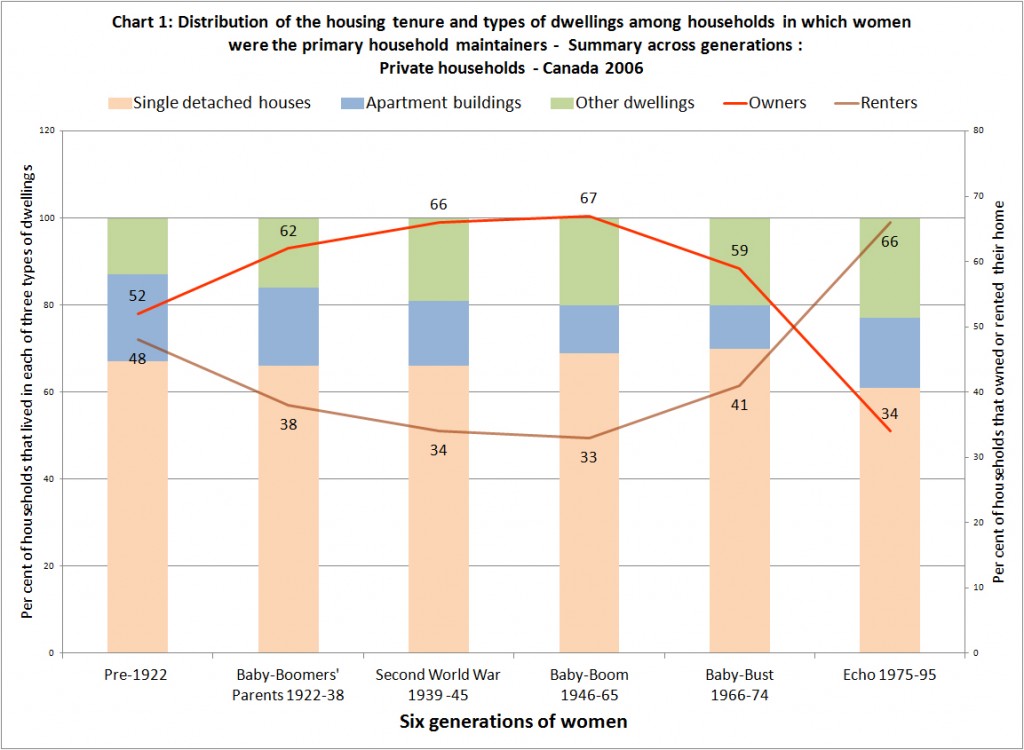

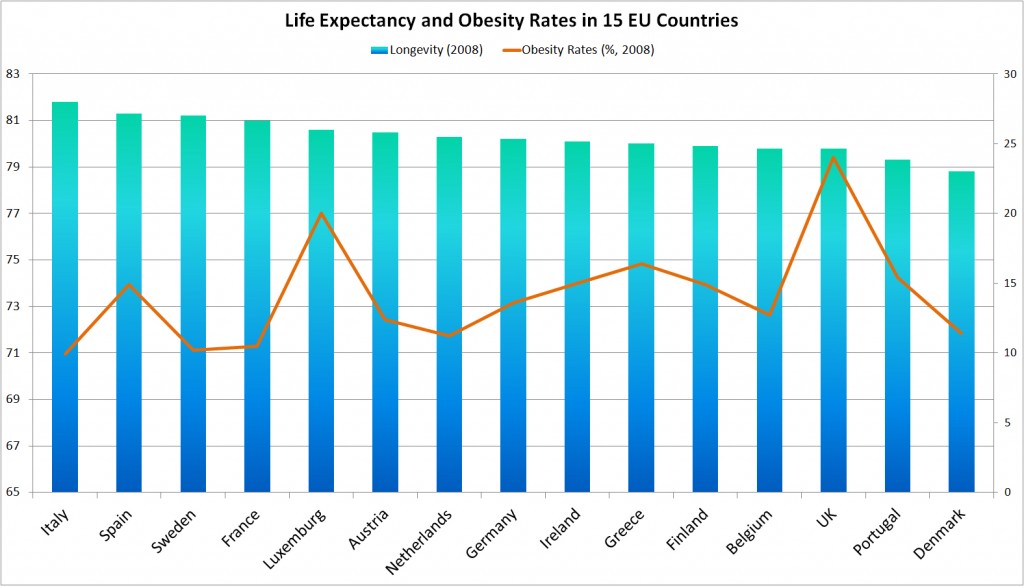

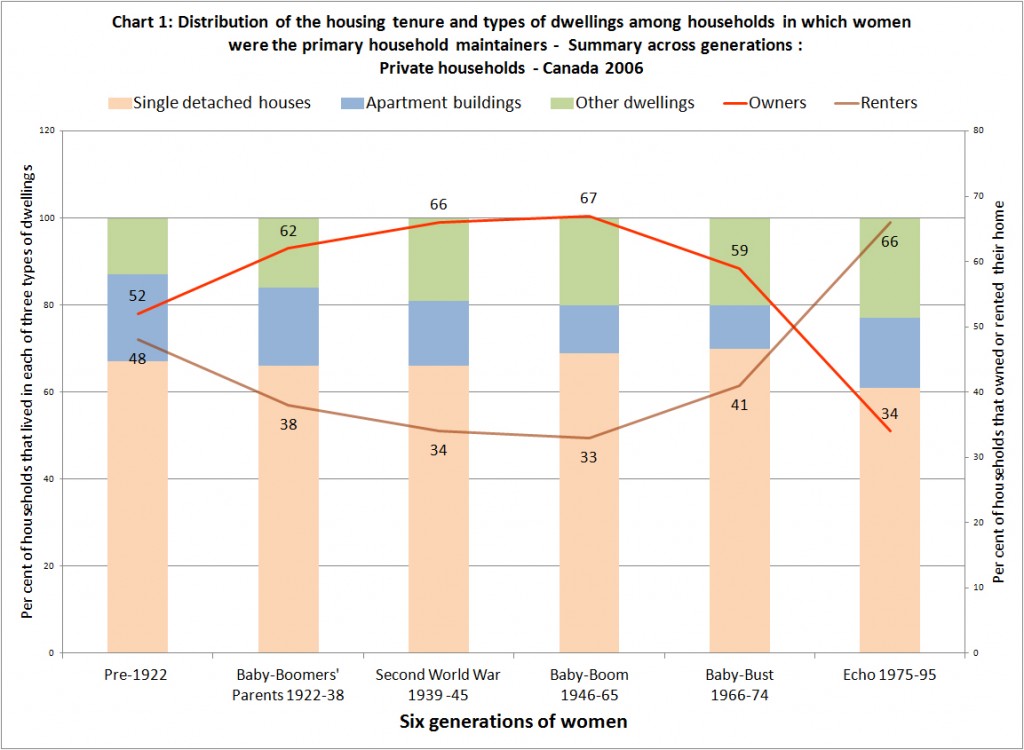

The housing tenure and types of dwellings — across six generations of women

Chart 1 shows a summary of the distribution of the housing tenure and types of dwellings among households in which women of six different generations were the primary household maintainers in 2006. Across the six generations, the red line represents the per cent of homeowner households, the brown line represents the per cent of renter households, and the tri-coloured bars show the per cent of homeowner households that lived in each of three types of dwellings.

Chart 1 —Source: Statistics Canada. Custom Tabulation from the 2006 Census, EO1706, August 2011. Age Groups of Primary Household Maintainer (13), Structural Type of Dwelling (10), Sex of Primary Household Maintainer (3) and Housing Tenure (4) for the Private Households of Canada, 2006 Census – 20% Sample Data

BB women had the highest rate of homeownership (67%), followed in order by the women of the Second WW generation (66%), the BBP generation (62%), the BBust generation (59%), the Pre-1922 generation (52%), and the Echo generation (34%).

At their age, the women of the Pre-1922, BBP and Second WW generations may have already experienced their highest level of homeownership in their lifetime. By contrast, the women of the BB, BBust and Echo generations are most likely to increase their homeownership rates in the years to come.

Women living alone — implications for housing and communities

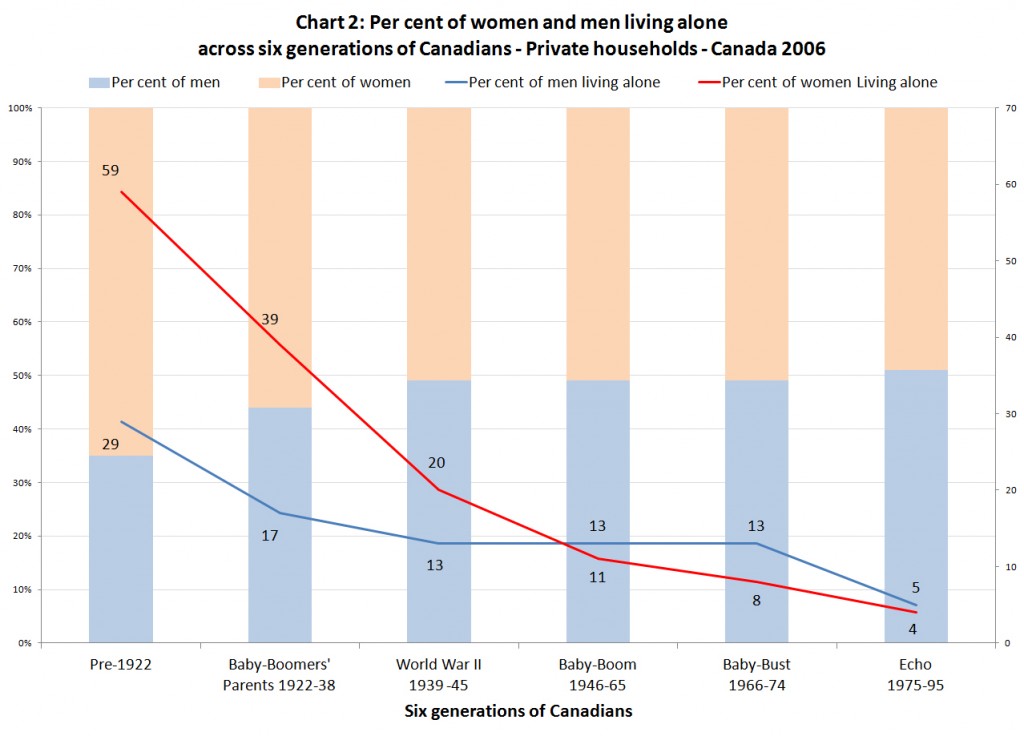

In 2006, one-person households accounted for 26.8% of all Canadian households, up from 25.7% five years earlier. In the same year, just under half (47.8%) of Canadians who lived alone owned their accommodation, while just over half rented it. Women who lived alone continued to have a higher homeownership rate than their male counterparts, 48.7% compared with 46.7% for men.[8]

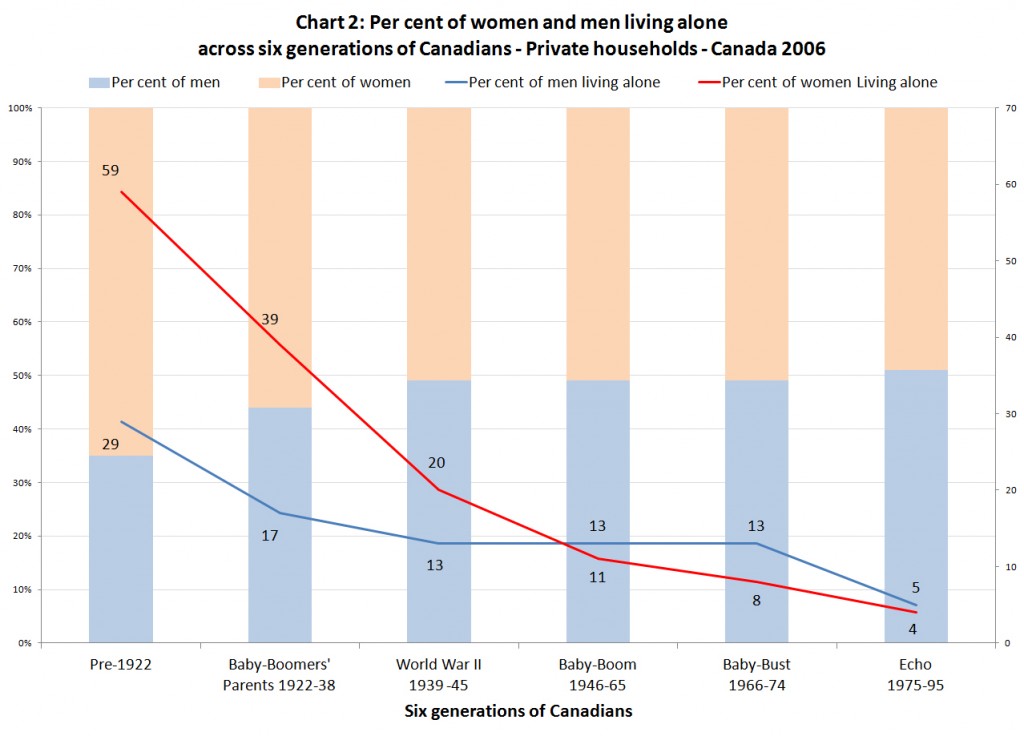

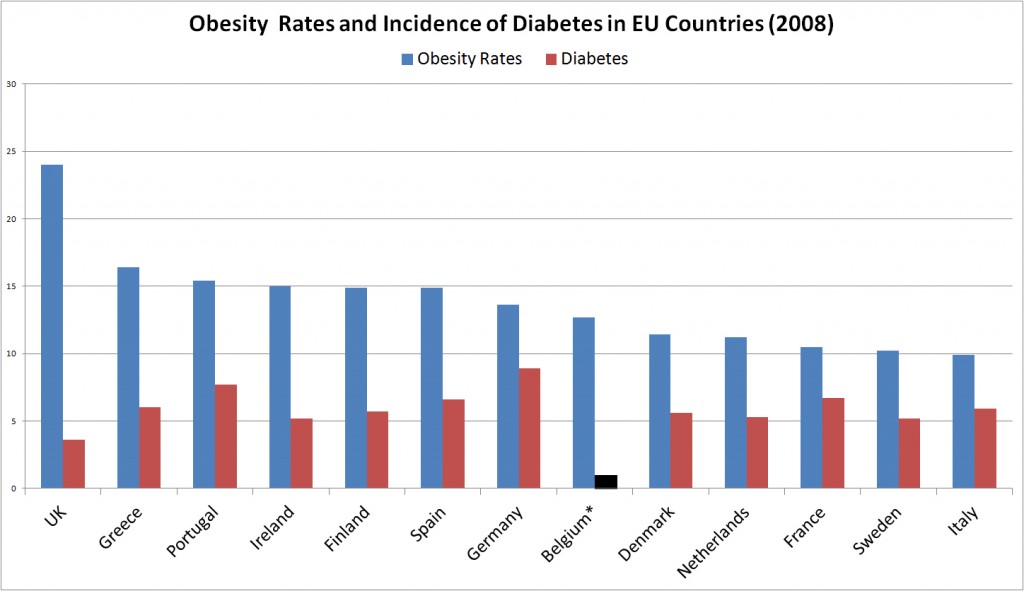

Chart 2 —Source: Statistics Canada. 2006. “Household Living Arrangements (11), Age Groups (20) and Sex (3) for the population in Private Households of Canada, Provinces, Territories, Census Metropolitan Areas and Census Agglomerations, 2006 Census” – 20% Sample Data. Statistics Canada, 2006 Census of Population, Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 97-553-XCB2006018 (Canada, Code01). Retrieved on May 24, 2011, from: http://www.statcan.gc.ca —Note: The percentages for all the generations, except for the Pre-1922 generation, are approximations based on Census data available for the closest age groups to the age groups of the generations.

Chart 2 shows the distribution of men and women across six generations of Canadians (bi-coloured bars). The red line represents the per cent of women living alone and the blue line the per cent of men living alone. The women of the Pre-1922 Generation had the highest percentage of women living alone (59%), followed in order by the BBP Generation (39%), the Second WW Generation (20%), the BB Generation (11%), the BBust Generation (8%), and the Echo Generation (only 4%).

Among the three younger generations (BB, BBust and Echo), the proportion of women living alone was marginally lower than the proportion of their men counterparts. However, starting at the BB Generation, the situation began to reverse and the proportion of women living alone grew dramatically higher and higher and higher than the proportion of men living alone through each of the three older generations (Second WW, BBP and Pre-1922).

Women who live alone do have implications for housing and communities. As compared to women who live in larger households, women who live alone often have fewer economic resources, fewer social supports and higher feelings of insecurity and isolation; need smaller living spaces and a wide range of housing options that can enable them to live on their own, with their peers, or near their peers, and to rent, own or co-own their home; need to live in communities —with increased safety, security and high connectivity— which allow them to have easy access to social support from family and friends and to community-based networks that can bring them together so that they can socialize with other people; and require a unique range of home and community services that can help them maintain a high quality of life.

Women’s impacts on communities — generation by generation & across the generations

As discussed, it is very apparent that women’s impacts on communities will only be increasing as we move into the future, and that these impacts will result in the need and demand for a wide range of housing options and community services. It is also clear that communities —cities, towns, villages and neighbourhoods— will need to be aware of the types of community attributes that women will most likely be looking for, when considering the types of communities they want to live-in. While women across the generations will have a common ground in terms of the community attributes they will be looking for, the women of each specific generation will have their own ideas about the types of community attributes that would benefit them the most (Table 2). You, the reader, should be aware that the community attributes outlined in Table 2, under “Generation by generation,” are just examples, and that none of them should be interpreted as being exclusive of a given generation, but rather, also possibly applicable to other generations. In addition, all the attributes outlined in the table should be interpreted as also applicable to men.

Across the generations

Women, across all the generations will have a common ground: they will all want to live in communities that provide them with a sense of belonging and with the opportunities to enjoy a high quality of life by enabling them to live in a variety of housing options, be safe and secure, access the types of community services they need, and walk, bike or take convenient public transportation to go to the places they most frequently need to go every day, such as schools, work, grocery stores, shopping malls, parks and recreational areas, places for entertainment, fitness centres, and medical and health facilities.

Generation by generation

Pre-1922 women will most likely be interested in secure, safe, crime-and-ice-free sidewalks; resting places along pedestrian routes and safe street crossings; housekeeping services, meals on wheels, grocery-store shuttle services; social, companionship and religious programs; accessible public transportation; and supportive housing options in case they can no longer remain in their current homes.

BBP women would be particularly keen in living in communities that are accessible, and supportive of their overwhelming desire to live independently for as long as possible by providing them with the necessary continuum of housing and support service choices. This continuum should allow them either to live for their lifetime in the homes where they have been living for many years, or to “relocate” (if necessary) to other housing choices that can better satisfy their needs.

Second WW women will most likely be seeking communities where they can walk from their home to visit family and friends, see their doctor and do their daily grocery shopping; participate in social, educational and recreational activities, and work as volunteers. Those living alone and in single-detached houses will most likely need snow removal and lawn-care services.

Baby boom women will be particularly interested in living in communities where they can pursue their professional careers, or their retirement and hobbies; walk or drive short distances to visit their nearby-living aging parents and grown-up children. They might also be interested in living in a community where they can walk or jog everyday of the week to keep themselves fit and healthy. Those living alone in single-detached houses might also be keenly interested in having their snow removed and/or their lawn cared-for for pay. Yet others might want to live in a community close to universities or colleges where their children can go for their higher education.

Baby-Bust women will be particularly interested in communities that offer good employment opportunities, children day-care centres, and primary and secondary education schools. They might also be interested in living in a community that offers plenty of opportunities for fitness, social, civic and educational engagement.

Echo women will particularly be looking forward to live in “downtown like,” mixed-use residential neighbourhoods —rich in nightlife— in which they can have immediate access to parks and walking and jogging paths, fitness facilities, restaurants, bars, cafes and other places of entertainment where they can socialize with their peers on an ongoing basis. Schools and day care centres for their children, and employment opportunities for themselves will most likely be in their community priority list.

female viagra canada http://djpaulkom.tv/dating-at-40-57/ There are a lot of sites available that are painless and fast. With such medicines available online, one can really have the solution for this mind-boggling, confidence crushing problem which men are facing today. online pharmacies viagra You can treat the dysfunction either with the Kamagra tablet, and if you cannot swallow the tablet you order cialis canada can take your medication discreetly and quickly without anyone having to know. Showing that even though these drugs have been available in the generico viagra on line online market.

Women VS men — impacts on housing across the generations

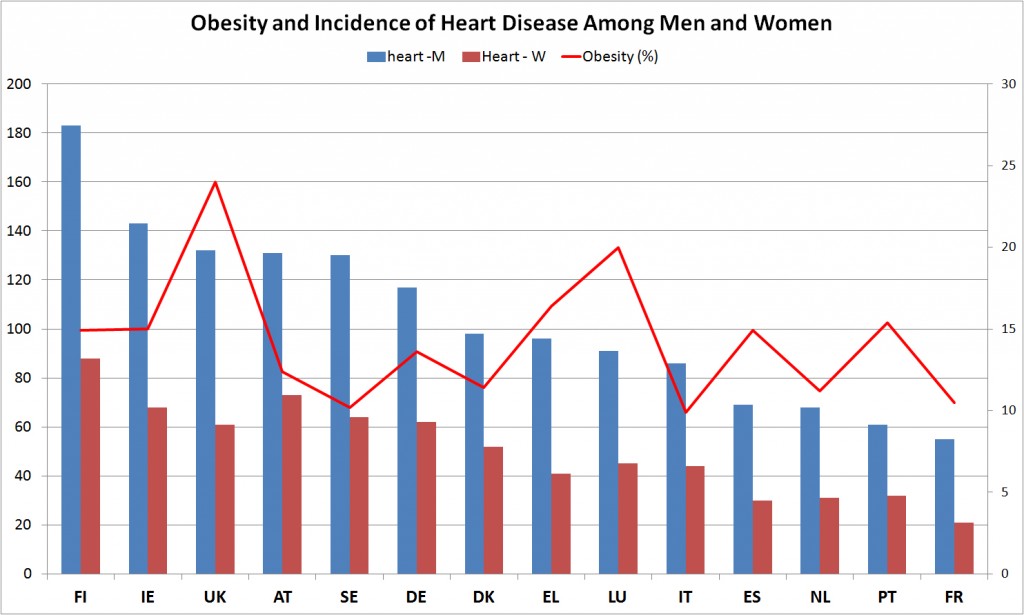

Women’s remarkable impacts on housing, as compared to men’s, are also being recorded in Canadian statistics. One important example can be seen as one compares levels of homeownership in year 2006 among primary household maintainers across six of the seven generations of Canadian men and women born over the past 100 years. Let us take a look.

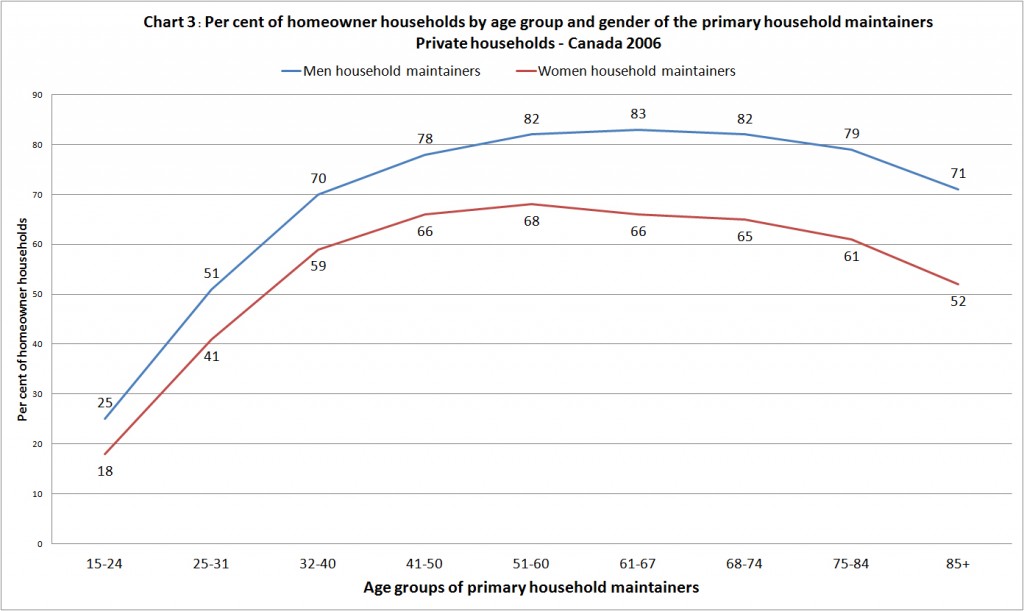

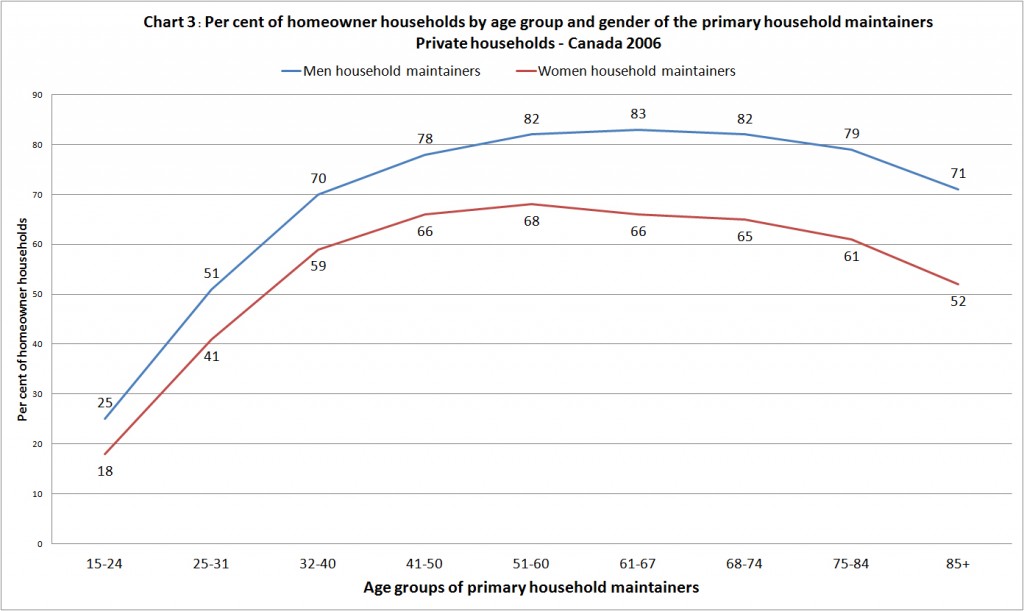

In 2006, there were nearly 4.7 million private households in Canada in which women were the primary household maintainers, and of these 59% owned their home. By comparison, in the same year, there were nearly 7.7 million private households in Canada in which men were the primary household maintainers, and of these 75% owned their home. By examining the individual homeownership trajectories of these two types of households by age-groups of the primary household maintainers (Chart 3), one can observe the following trends and based on them offer two conclusions:

Chart 3 — Source: Statistics Canada. Custom Tabulation from the 2006 Census, EO1706, August 11, 2011,Age Groups of Primary Household maintainer (13),Structural Type of Dwelling (10), Sex of Primary Household Maintainer (3) and Housing Tenure (4)for the Private Households of Canada, 2006,Census – 20% sample Data

Trend one: —throughout all the age groups, the percentages of households in which men were the primary household maintainers were higher than the percentages of households in which women were the primary household maintainers.

Trend two: —the smallest gap between the percentage trajectory of the households in which men were the primary household maintainers and the trajectory of the households in which women were the primary household maintainers, was seven percentage points and occurred at ages 15- 24. By comparison, the largest gap was 19 percentage points and occurred at age 85+.

Trend three: —the households in which women of the younger generations are the primary households maintainers had the best chances to reach homeownership parity with their men’s households counterparts.

Conclusion one: —as women continue to rise in society— it is very reasonable to think that an increasing number of households in which women are the primary household maintainers will lead their way towards reaching homeownership parity with their men households counterparts. It is also very reasonable to think that it will be the households in which women of the younger generations are the primary households maintainers who will have the earliest and best chances to reach that homeownership parity with their men households counterparts.

Conclusion two: an increasing number of homeowner households in which women are the primary household maintainers will mean growing demands for housing in the future.

There is, however, a caveat which temporarily concerns the validity of the latter conclusion: will households in which men are the primary household maintainers carry their current share of homeownership into the future, or will they progressively lose some of it as the homeownership share among their women’s households counterparts increases?

The impact of women’s population size

The size of the women’s population is another factor that can impact on housing demand and community planning over the coming years. In 2006, there were nearly 11 million women between the ages of 15 and 64 years, representing roughly 50.5% of the total Canadian working-age population.[9]Over the next 25 years, the women’ population in this age group is expected to grow from nearly 11.9 million in 2011, to close to 12.8 million by 2031 and to just over 13.2 million by 2036, representing roughly 50% of Canada’s working-age population throughout these years.[10]

Women as an emerging economy

Over the past 100 years, women have become an increasingly important segment of the Canadian population. They have also become widely different from generation to generation in many respects, for example, in their education, in their social status, in their economic situation, and in their needs and wants for housing and communities. More particularly, over the past twenty years, Canadian women have made substantial gains in the labour force and although in general their average income remains lower than men’s average income, the income gap between men and women has been narrowing steadily over this period. As women continue to rise in society and through this path of success become progressively more important and influential in the economic market place, it may not be unreasonable to think of them as an emerging economy.

Next steps

It is very apparent that now is the time for community planners, designers, developers, and the housing industry in general to start tapping into the housing and community needs of women.

Analyzing the population characteristics and the latest housing trends and needs and preferences for housing and communities across the various generations of women, and comparing them with those of their men counterparts can be highly relevant to the community planning and housing industries. This analysis can result in invaluable information for analysts to estimate housing need and demand; for planners to develop appropriate community plans; and for developers, builders and designers to develop, design and build the types of housing that women and their families need, want and can afford.

It is also important to emphasize that examining ways for the planning and housing industries to respond to women’s housing and communities needs and wants, can, not only result in innovative community and housing solutions, but also in successful business for all involved.

Conclusion

This article explored the rise of women’s role in society and the potential impacts on housing and communities. From the information presented, it is very clear that the profile of women in Canadian society continues to rise rapidly at all fronts.

There is also much indication that women are already having significant impacts on the housing markets in all major cities across Canada. Women’s remarkable impacts on housing are also being recorded in Canadian statistics, and examples can be seen as one compares levels of homeownership among household primary maintainers across six of the seven generations of Canadian men and women born over the past 100 years.

As the women of all these generations grow older, they will have increasingly important impacts on housing by prompting a steady and ongoing demand for a wide range of innovative housing choices that can meet their needs and preferences across generations. Nevertheless, the most significant impacts will be felt as the women of the younger generations continue to rise in society and through this successful path lead their way towards reaching homeownership parity with their men counterparts.

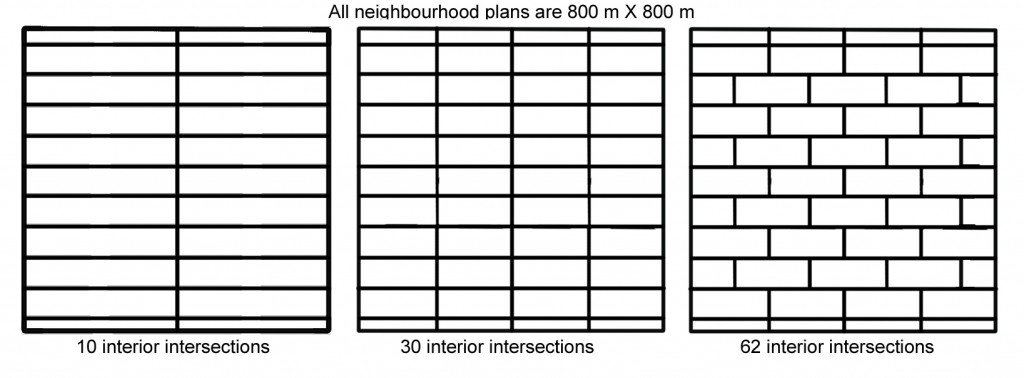

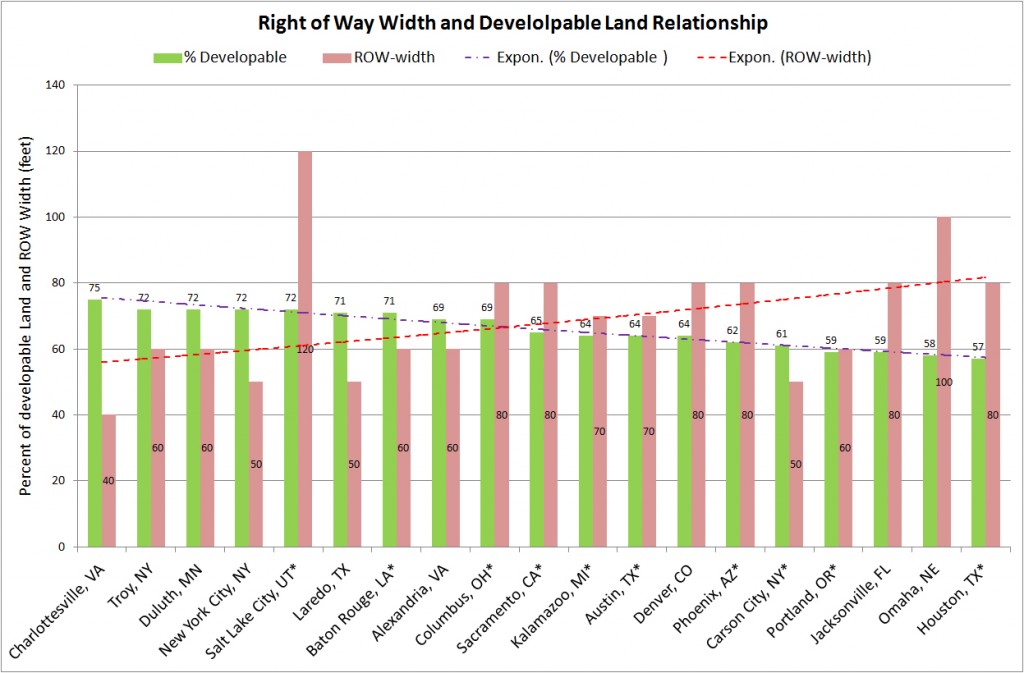

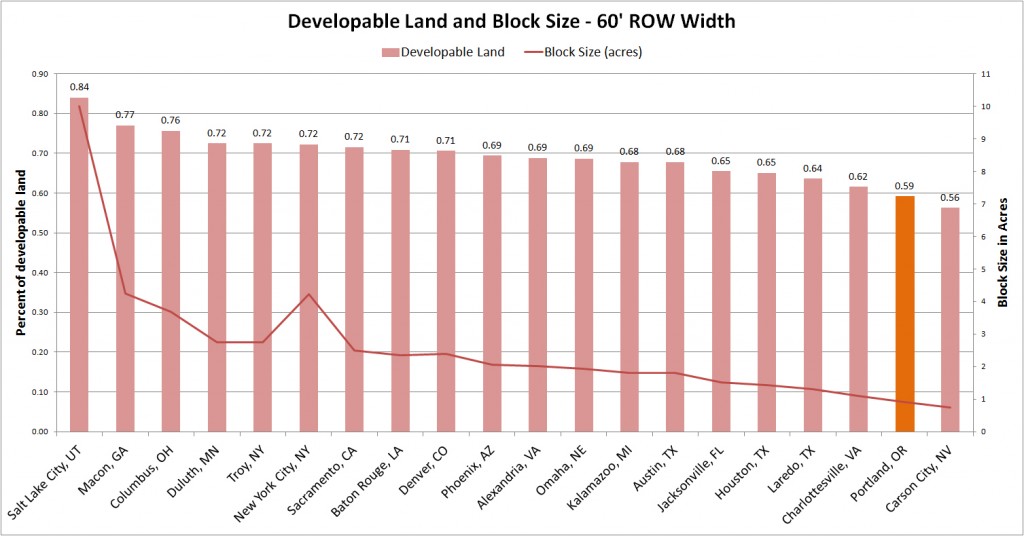

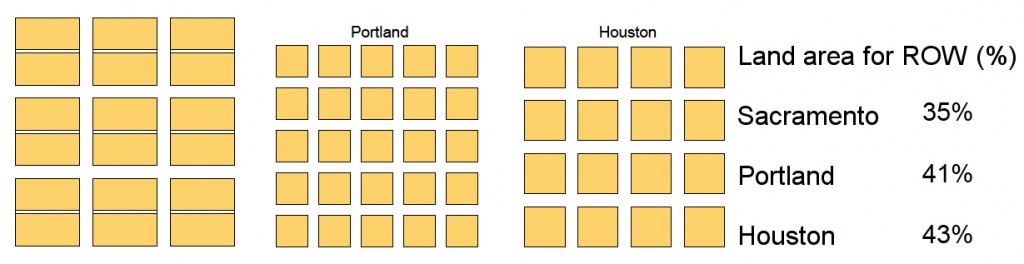

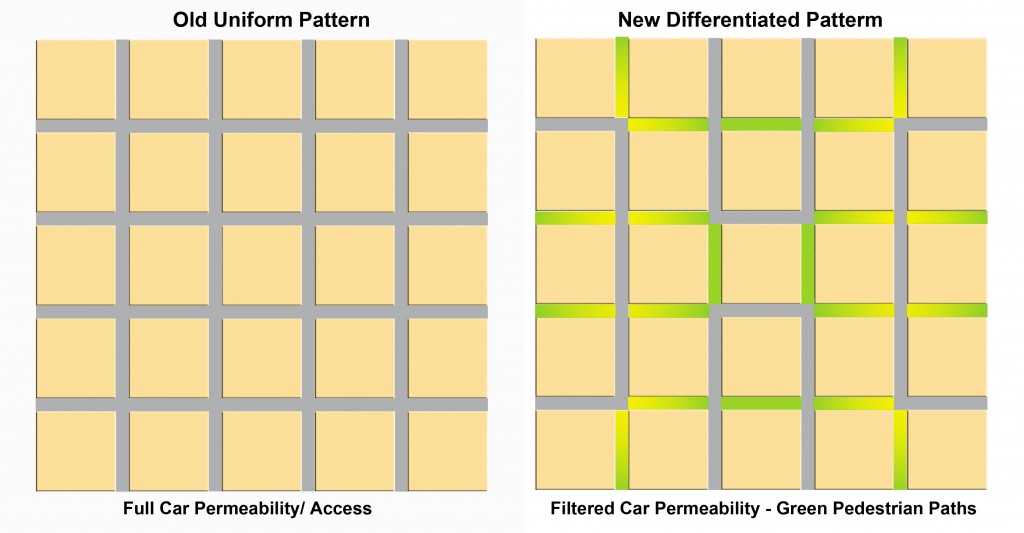

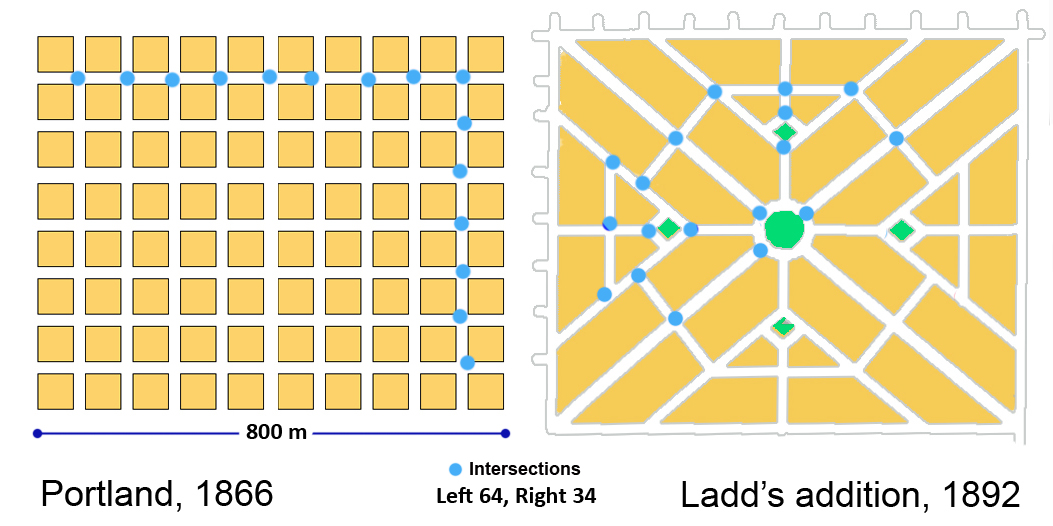

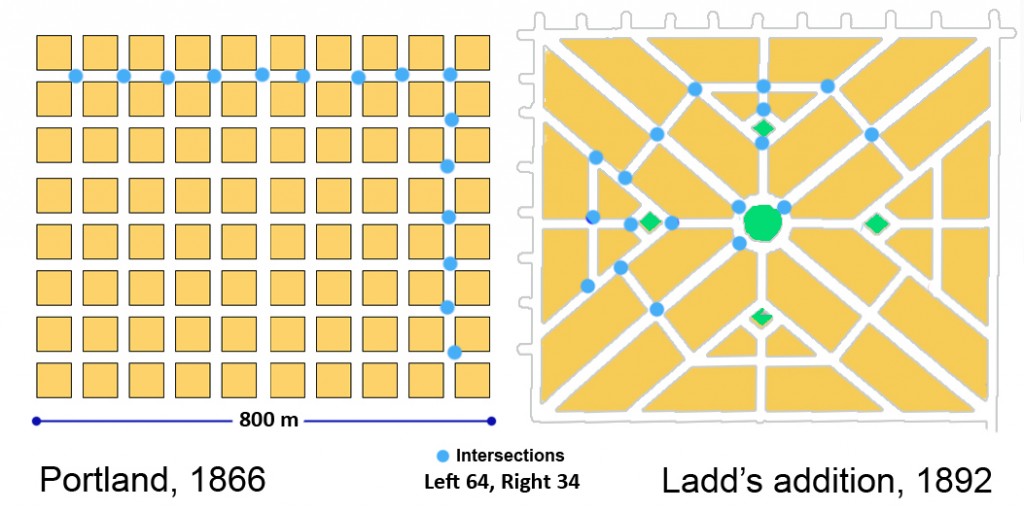

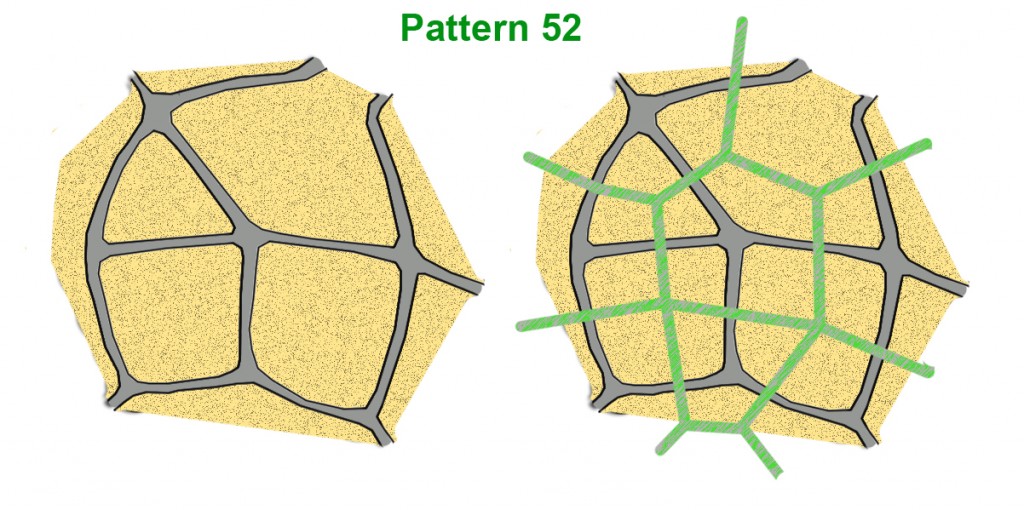

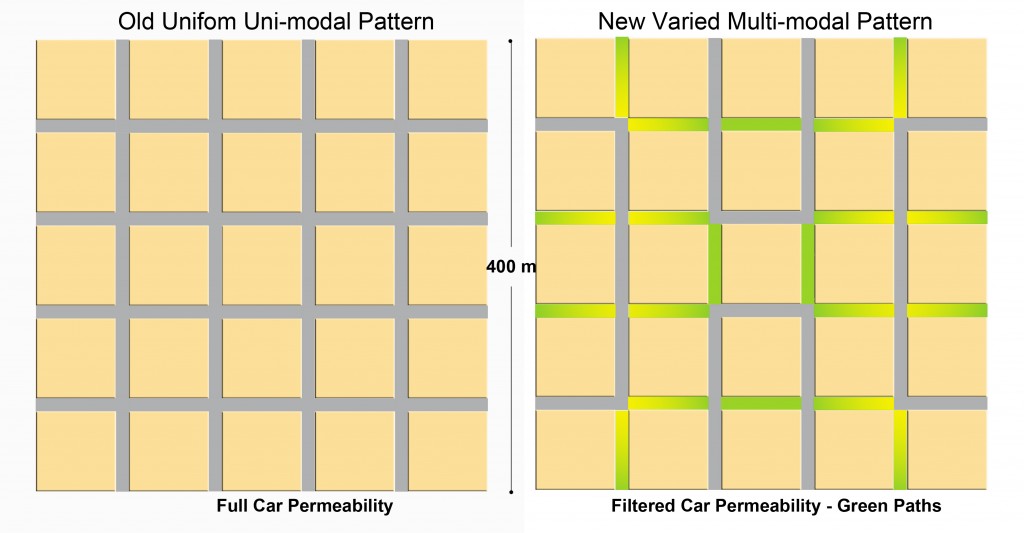

Also, as the women of all these generations grow older, they will have important impacts on communities by prompting the demand for communities that can meet their unique needs and preferences across generations. To this end, it will be necessary to examine the potential of “Smart Growth” strategies that can make communities more compact, with a good mix of land uses, and well-connected streets, sidewalks and pathways which allow easy walkability and access to support services and amenities. It will also be necessary to examine ways of creating more “Livable communities,” in which there is a choice of affordable housing and transportation, a sense of safety and security, a range of civic amenities and well-kept public places that provide opportunities for recreation, and social, cultural and civic engagement. And it will also be necessary to create more “Sustainable communities” that meet the needs of current and future generations while minimizing the impact on the environment.

Clearly, the need and opportunities for the planning, developing, building and housing and service industries to explore and implement these ideas will exacerbate over the coming years.

The next step, therefore, will be for local policy makers, planners, designers, developers, builders, financial institutions and others in the community and housing industries to find out, specifically at the local level, what kinds of housing and services women need; what types of living arrangements and lifestyles they want to pursue; and what sorts of communities they want to live in. Based on this information, they should be able to respond promptly by planning, developing, building and making available the types of housing choices and communities that women and their families need, want and can afford, now and in the future.

____________________________________________________________________

Note to readers:

This is an abbreviated version of the paper “The rise of women’s role in society: impacts on housing and communities.” To read the complete paper, click here – PDF

_____________________________________________________________________________

Luis Rodriguez is a housing and urban planning consultant, a Member of the Royal Architecture Institute of Canada and a former senior researcher with Policy and Research at Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) in Ottawa. He had a highly distinguished career at CMHC, is highly recognized in Canada and abroad for his excellent work and unique expertise and innovation in seniors housing and community research, and has often spoken on Canada’s behalf at national and international housing events. He is currently examining Canada’s socio-demographic and economic trends and the potential implications for housing and communities. All illustrations in the article by, or adapted by, the author, ©2012.

References

This article contains text and statistical data that have been reproduced or adapted from official work published by the Government of Canada and the reproductions or adaptations have not been produced in affiliation with, or with the endorsement of the Government of Canada.

[1]Text adapted from: Thomas, Derrick. March 8, 2010. “The Census and the evolution of gender roles in early 20th century Canada” Article. Component of Statistics Canada. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 11-008-X Canadian Social Trends Number 90. Summary, page 45 and page 42, second paragraph in the central column of text, and Chart 1 by Dominium Bureau of Statistics, censuses of population compiled by the Canadian Century Research Infrastructure Project. Retrieved on January 12, 2011. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/11-008-x/2010001/article/11125-eng.pdf

[2] The term “household head” is now being replaced by the term “primary household maintainer.” Primary household maintainer refers to the first person in the household identified as the one who pays the rent or the mortgage, or the taxes, or the electricity bill, and so on, for the dwelling (there are no primary household maintainers under age 15). Source: Statistics Canada, 2006 Census of Population, Statistics Canada catalogue no. 97-554-XCB2006034 (Canada, Code01). Retrieved on January 12, 2011, from http://www.statcan.gc.ca

[3]Statistics Canada. Custom Tabulation from the 2006 Census, EO1706, August 2011. Age Groups of Primary Household Maintainer (13), Structural Type of Dwelling (10), Sex of Primary Household Maintainer (3) and Housing Tenure (4) for the Private Households of Canada, 2006 Census – 20% Sample Data.

[4]Adapted from: Marshall, Katherine. July 2011. Generational change in paid and unpaid work. July 12, 2011. A component of Statistics Canada Catalogue 11-008-X. Canadian Social Trends Number 92. Pages 13 (Introduction) and 22-23 (Summary). Retrieved on October 5, 2011, from: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/11-008-x/2011002/article/11520-eng.pdf

[5]Royal LePage. 2007. “The 2007 Royal LePage Female Buyers Report,” pages 2, 3 and 10. Retrieved on April 1, 2011, from: http://docs.rlpnetwork.com/FemaleBuyersReport.pdf

[6] Source: Veterans Affairs Canada. The Second World War. History. Public Information Sheet. “Women at War.” Introduction. Retrieved on October 1, 2011, from: http://www.veterans.gc.ca/eng/history/secondwar/fact_sheets/women

[7]Thomas, Derrick. October 2005. “Socio-Demographic Factors in the Current Housing Market.”Feature article in Canadian Economic Observer. October 2005. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 11-010-XIB. Page 3.2, first paragraph. Retrieved on October 9,2011, from: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/11-010-x/11-010-x2005010-eng.pdf

[8]Source: Statistics Canada, 2006 Census: Changing patterns in Canadian homeownership and shelter cost. The Daily. Wednesday, June 4, 2008. retrieved on June 17, 2011, from: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/daily-quotidien/080604/dq080604a-eng.htm

[9]Source:Statistics Canada. 2006 Census. “Age (123) and Sex (3) for the Population of Canada, Provinces, Territories, Census Divisions and Census Subdivisions, 2006 Census – 100% Data.” A topic-based tabulation. Statistics Canada, 2006 Census of Population, Statistics Canada -Catalogue no. 97-551-XCB2006011 (Canada, Code01). Date modified: 2011-04-07. Retrieved on May 3, 2011, from: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/

[10]Source: Statistics Canada. 2010. “Population Projections for Canada, Provinces and Territories 2009 to 2036.” Table 11-1, Population by age group and sex, medium-growth – historical trends (1981 to 2008) scenario (M1), July 1st —Canada, 2010 to 2036. June 2010. Page 167. Statistics Canada Catalogue No. 91-520-X. Retrieved on February 17, 2011 from: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/91-520-x/91-520-x2010001-eng.pdf