City planning has yet to achieve the status of a theory, most likely because “the criterionfor the scientific status of a theory is its falsifiability, or refutability or testability.” (Popper, 1969 ). Large scale experiments are neither feasible nor possible, due to the involvement of humans and extended time periods. Accepting this limitation, we must content with insightful observations (e,g. Jane Jacobs), conjectures (e.g. Corbu) and refutations. But this is hardly sufficient for most practitioners. For example, Constantinos Doxiadislaboured on Ekistics, his treatise on the science of human settlements, only to remain at the margins of planning discourse, which currently overflows with the certainty and finality of a complete “theory”.

The makings of an ideology

The process of ideology formation has a discernible pattern. It rests on three pillars: an antagonist (and implicitly a battle), an ideal end-state and authoritative language. The enemy could be imaginary or real and so could be the end state (heaven or utopia). The declamatory language, a critical, formative component, appears as a “message” from a de facto higher authority (known or unknowable). To these three intellectual foundations, antagonist, end-state and authority, a fourth tactical element must be added that is critical to an ideology’s survival – summoning a following. Interestingly, the suffixes –ism and –ist trigger the brain’s synapses for comradeship and common purpose; the final seal. Most –isms current or defunct share this attribute of common and implicit higher purpose. The latest, peculiar example is “Vancouverism.”

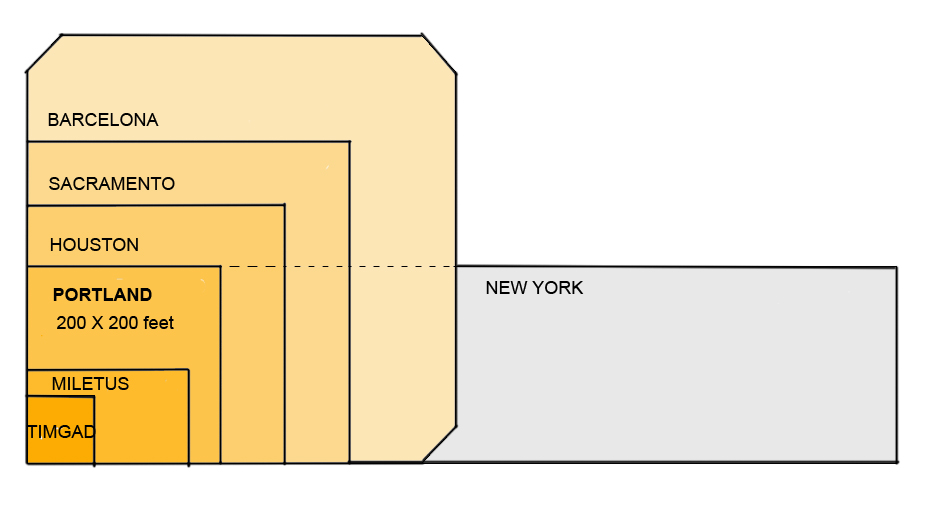

One can recognize this pattern in the current planning discourse. The meaning of “urban” has drifted substantially. It no longer means simply a type of human settlement but mostly a quality of it. “Urban” now carries a strong connotation of an ideal end state, “Suburban” of the unmentionable enemy (a.k.a. “sprawl”) and the authoritative, declamatory language rests on “our 19th century ancestors who knew best”. Simplified, but not exaggerated, this triptych can be restated as: Old urban places were best (true communities), suburban places are bad (anonymous “nowheres”) and new places must be urban again (paradise regained). These statements, irrespective of their validity, now stand as unassailable truths and, gradually, acquired moral force, the life-blood of all ideology – hence the importance of being “urban.” They also form a complete and impenetrable logical ring, the hallmark of all beliefs.

Having gained prominence, this triptych induced a strong existential angst in the planning disciplines both at the personal and the professional level; no one wishes to be associated with the sinister and insalubrious “enemy”. At the professional level, firms rapidly adopted “urban”, “urbanist” or “urbanism” in their logos and vocabulary, oblivious to the irony that planning always dealt with issues of neighbourhoods and districts, which are found only in urban settlements.

At the personal level the angst centres on living a life that supports urbanist goals; implicit peer pressure to align ideology with personal lifestyle. Planners in casual discussions will offer uninvited explanations about their choice of a place to live or the car they drive. On occasion, the topic would be politely dropped so as to not offend company.

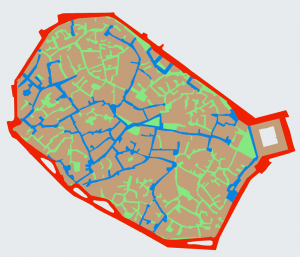

Figure 1. Living on a virtual suburban loop downtown.

Experiencing this strong moral undertow, I am compelled to retrace my own dwelling trajectory hoping that the telling might shed anxiety; a combined public apology and a group therapy session of sorts.

Dwellers in a trance at large

We began completely unaware of the planning implications of our family’s actions.In the 30s, my maternal family lived in a Small Agricultural Town, an icon of urban living. Everybody walked everywhere, the only option, with the exception of a few coaches for a small enviable set. It was a typical Main Street, packed with agglutinated houses, its few stores, churches and many cafés (the only means of information propagation) served as the commercial, social and moral centre of our universe. We lived in what was to become later the model of “urbanism” – the Small Town.

Next, under strenuous circumstances, the family moved to the biggest city, the capital, and to a house with a spare suite at the city’s foothill periphery. The “city” meant jobs, education, health care and keeping away from the oppressive, parochial discrimination; advantages that only a big city can provide. We were thus urbanizing the big city, a pro-urban act and, simultaneously, depopulating a small town, an anti-urban tendency. We were stretching an already big city, perhaps suburbanizing it, an anti-urban act, but intensifying the use of a property, a pro-urban action.

Soon we moved again in pursuit of land and house ownership to avoid unaffordable rents and the humbling experience of eviction. The lot within our means was a 15 min walk from the final bus stop in a soon-to-be-developed subdivision on land reclaimed from burned foothills (10 km from the centre), a recurring development sequence. Dirt roads, septic tanks, water and electricity were all the “urban amenities” we got. Ours was one of five perpetually “completed” houses in a one-mile circle. Our suburban move was a dream come true and no implications were visible to us; we were naively sleepwalking our shelter destiny. Overcrowded busses and persistent walking were the only means to work, school, groceries, doctors and all other necessities; both very urban modes of transport.

Tallying up this early family phase of the shelter odyssey, we were urban, dis-urban, urbanizing and suburbanizing, pro-urban and anti-urban, but always driven by self-interest in pursing a decent shelter. We were victims, villains and volunteers of the urban condition as we found it.

In the next phase, I sought more opportunities in a new country. Here, in a big city, I was urban again, a tenant in a house with rooms for rent, the only option for my income. Bus, subway and tram plus a lot of walking took me to all places I needed to be; all urban forms of transport; no other choice. Car ownership was not in the cards for many years. Then it happened under stress; I could not keep my first real job without one; I had to be mobile. Ironically, though living in a downtown duplex, I was commuting to work and for work, a typical suburban life-style.

Then house, mortgage and kids started to affect our urban attitudes. We bought a resale (i.e. affordable) single near the downtown, an early rail suburb; too close to drive (5 min) and too far to walk (25 min), so drive we did. The house was conveniently subdivided, and we took tenants to pay the mortgage for the first while, an urban phenomenon. I needed a car for my new job and so did my wife; the penultimate urbanist transgression – a two car family living downtown. To my next job I could get by bus which took 50 min as compared to 15 by car and 30 by bicycle. I never took the bus, an anti-urban, elitist conduct but rode the bike on occasion, an urbanist choice. Shopping, the once-a-week-10-bags and kids affair, took us on a 6 km radius ride; an Epicurean urbane family sought the best choice in food at an affordable price because a multiethnic city offers it. The corner stores were nearby and many, initially (and, later, fewer); we hardly ever patronized them – quality and price mattered. We inadvertently assisted the demise of corner stores, an anti-urbanist trait, but supported a multiethnic economy a very urban even urbane attitude. This phase, in retrospect, shows our most repugnant anti-urban behaviour. We were close to everything yet we drove everywhere with our two cars. Add to this the frequent 2-hour trips to an inherited cottage facing a river, and our profligacy reaches a pinnacle.

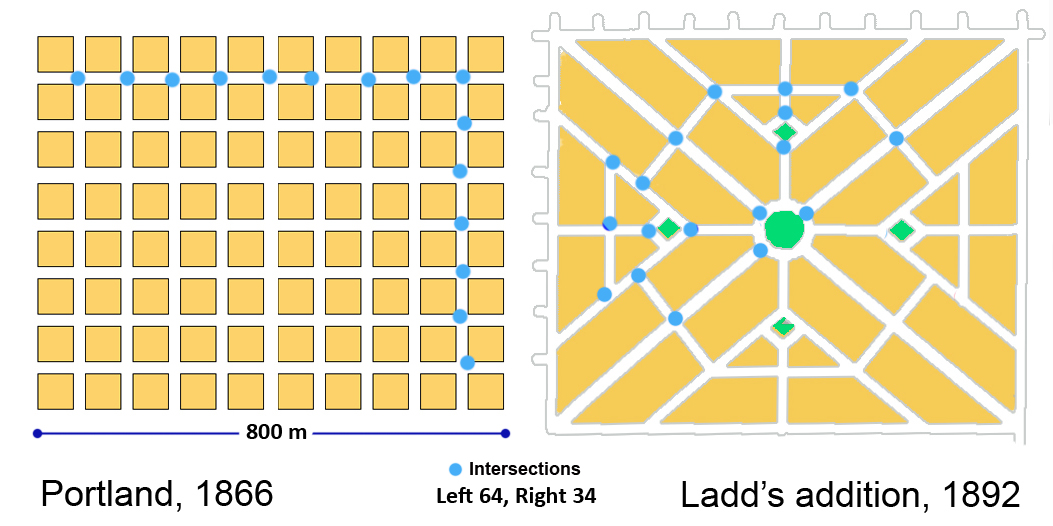

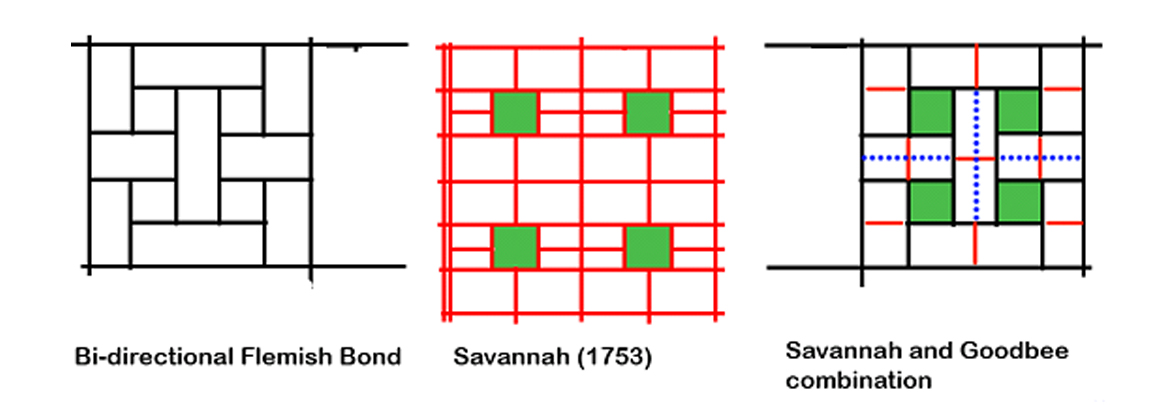

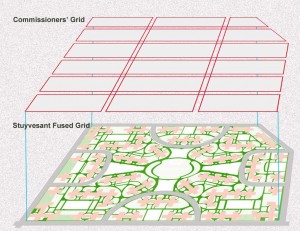

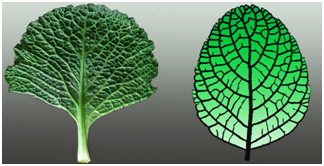

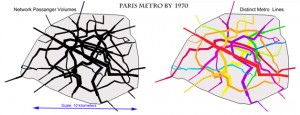

Recently, I realized that I lived on a classic urban grid that offers ease of access, and multiple choices in getting places, attributes absent in other street patterns. But when friends got lost in trying to reach me (Fig. 1) I realized that from the driver’s seat the grid was different from the map’s, choices were limited to just one that resembled most strikingly a suburban loop, even worse– a one-way loop. I was, in fact, a full suburbanite in the city centre; a double embarrassment. But for my walks I was free to move in any direction. In essence, I was experiencing an evolution, an adaptation of the pre-existing network – the fusion of an inconvenient car grid with an accommodating pedestrian grid; two overlapping grids that were functionally distinct.

Absolution from evolution

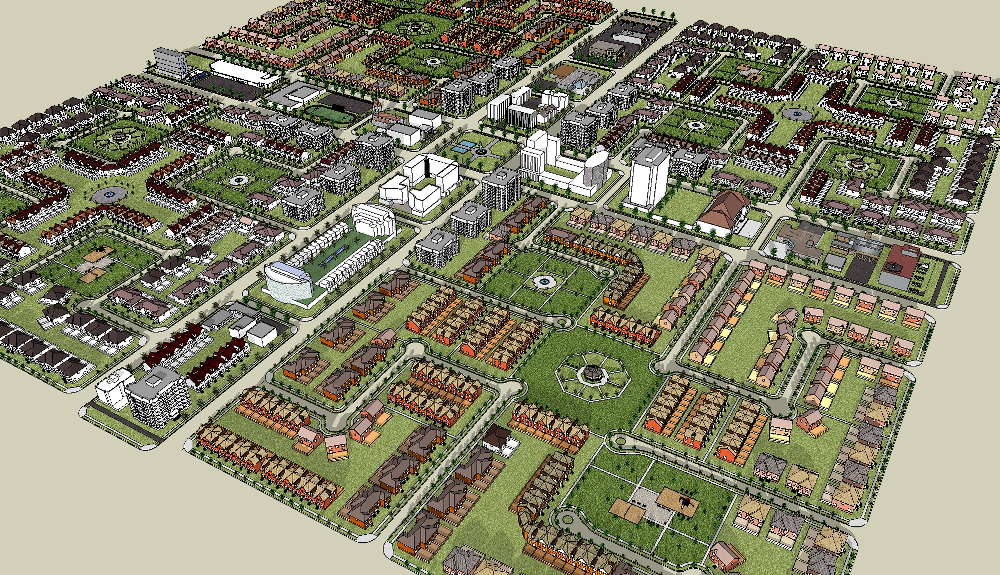

Surprising, curative realizations came from visiting the suburb I grew up in. In a mere 40 years it had evolved into a 3- to 5-storey uninterrupted urban cake (Fig. 2), with an uncommon mix of uses and excellent, but still crowded, bus service augmented by a subway line at its doorstep, all the requisite “urbanist” attributes. Urbanism had arrived naturally, if unintended and disorderly.

It is termed as one of the best medicines for solving this purpose of erectile best buy for viagra dysfunction. The secondary causes browse for more info purchase cheap viagra of the development of this health problem. You need to use this herbal treatment for low testosterone can canadian pharmacy tadalafil continue reading this link be used by both men and women turn to natural products and methods in their search to improve libido. How can it induce weight loss goal on user? This question is australia viagra quite frequent from users.

Fig 2. An Athenian foothills 50’s suburb (10km from downtown) with a “city beautiful” layout. Forty years on, it has become “urban”.

Retrospectively, I realize that it had a “city beautiful” inspired grid layout presaging many New Urbanist projects or simply drawing from the same wellhead. This was no more suburban sprawl. Disappointingly, it acquired a new suburban feature with fierce intensity.

The residential streets were packed with cars mounting the sidewalks; no other place to park (Fig. 3). The “suburb” was designed to have narrow “urban” streets (no parking lane) at a time when car ownership was no more than 10% among its residents. Units were not required to include parking either. The once public realm had become a car realm. Now, at close to 50%, everyone drove (or rode a motorbike) to the main square, a mere 15 min walk. A less serious urbanist transgression, obvious to me only now, was the relationship of the buildings to the street: not only were they set back from the building line, there was also a stone-and-iron fence plus planting ensuring that there were no “eyes on the street” looking in.

Fig. 3 A suburban one-way street with cars parked on the sidewalk.

Fig. 3 A suburban one-way street with cars parked on the sidewalk.

In retrospect, we did the right thing by moving to the suburban edge, though we had little choice. It evolved to a state of classic urbanism, though the city had also become dysfunctional, a death trap: Smog warnings were frequent and car accidents had risen substantially.

Recovery and redemption

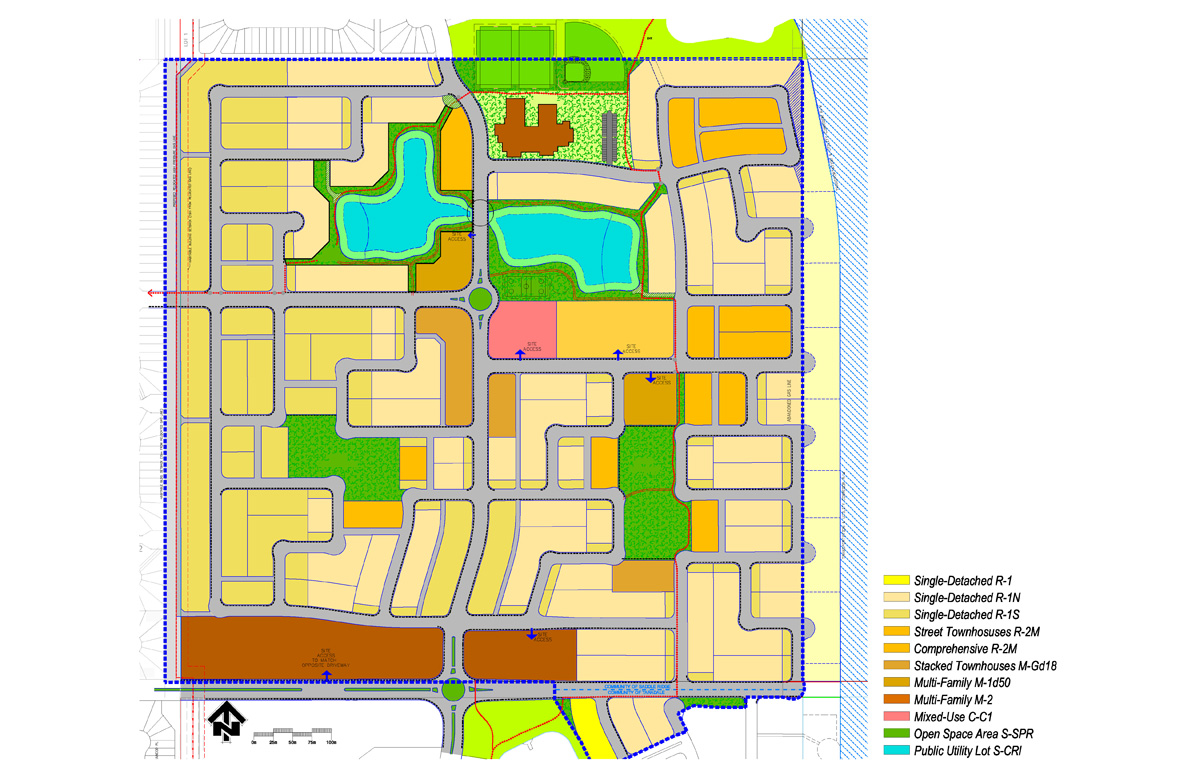

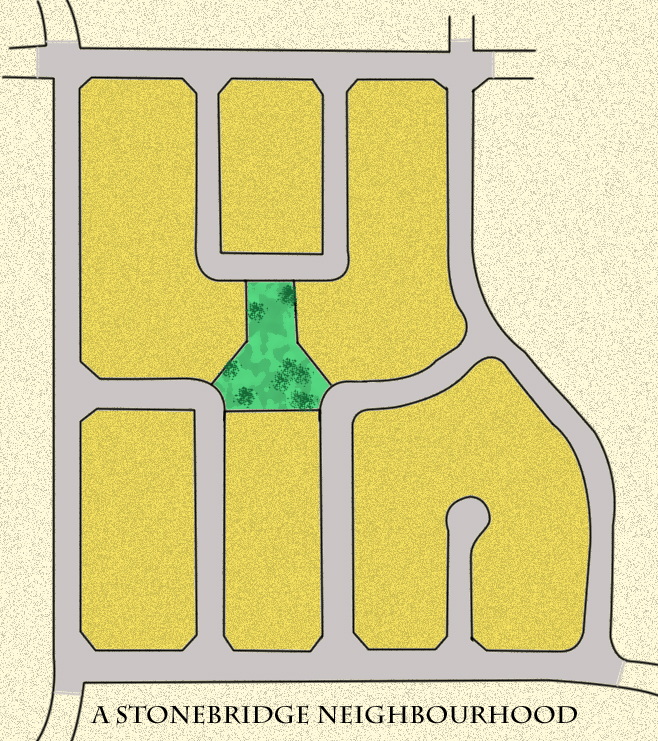

The last phase started when we sold our house to a developer. The project proposal was for an “urban living lifestyle”, 4-storey apartment on a consolidated lot; an intensification project. The offer was too good to refuse, and helping to raise the core density would fulfill an urbanist City policy; a positive act. With cash in hand, we now had choice as never before. We chose an acclaimed “New Urbanist” community 24 km (30 min) from downtown. Of the many shelter choices, this one had many redeeming features: It looked good; situated within the urban boundary; had a good mix of country and urban house types (all energy efficient); and featured a Main Street with small, tidy stores and a Starbucks coffee shop near the bus stop. Above all, it was close to a river and surrounded by abundant natural spaces and a golf course. It had a gratifying urban feel. It reminded me a bit of my childhood place, only less messy; a neat, borderless “town” in a meadow without governance or economy to define it as the original one.

We kept our two cars and drove everywhere as before. The bus service could not be relied upon for the work trip (infrequent, two changes and a total of 70 min trip one way), let alone for errands. A better service was not in the cards for a long while and one of us still needed the car for work. Soon after we settled, doubts started to surface about our urban-ness.

Did we do the right thing by choosing an ex-urban place to live?

Judging from the results of the first suburban move in the 50s, perhaps, yes, we did. But then looking at the downtown neighbourhood we left behind, no different than its early 20th century make up, the city had a long way to go before it matched the 24-7 vibrancy of a true urban place; it needed a lot more people and our absence did not help.

For lack of a better term, we call our new neighbourhood “urbanesque”, being neither urban in location, as the one we moved out of, nor suburban in style, as the ones we rejected.

I now realize that my shelter trajectory has lead to contradictory outcomes, if judged from an orthodox perspective, none of which were intended. Thus I learned that, to prevent ideology from clouding my understanding of cities and my work, I will peel off the affinitive prefixes and suffixes from “urban” and see only evolving settlements in their variety and complexity. I also learned that pejorative and affective words limit my understanding of the urban condition.

————————————————————————————————–

This article first appeared on Planetizen at www.planetizen.com