Goodbee Square, a recent project by Duany Plater-Zyberk and Company constitutes a fertile departure from previous DPZ plans, integrating novel elements of traffic flow, pedestrian movement, traffic safety, park allocation and distribution and storm water management into the regularity of a simple grid. As a change in direction, and because street patterns are the most enduring physical element of any layout, it could potentially contribute to systematic site planning and, consequently, deserves a closer look.

The street pattern

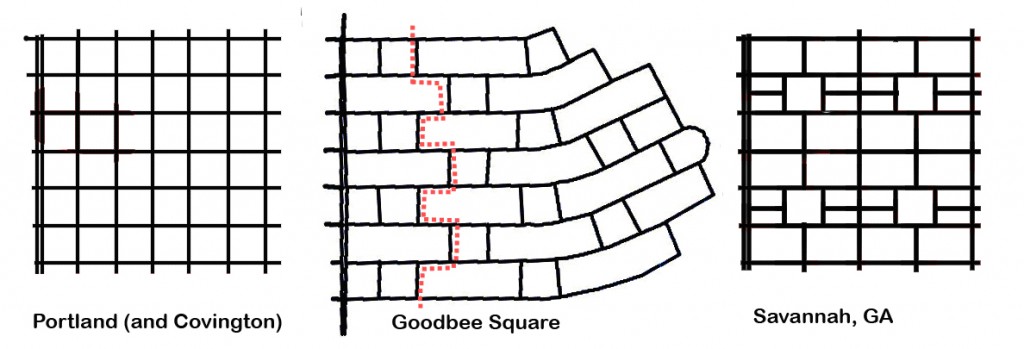

Unlike the classic street grid of Portland (Fig. 1, left), the Goodbee Square street layout (Fig. 1, center) impedes north-south vehicular and pedestrian movement, although pedestrians are given another option (Fig. 2). Though the network is entirely interconnected, north-south movement becomes circuitous, indirect, and inconvenient, making driving an unlikely choice and vividly illustrating that interconnectedness by itself is insufficient to facilitate movement. The 3-way intersections limit through traffic, a lesson incorporated in TND (Traditional Neighborhood Development) and reminded of recently at Seaside.

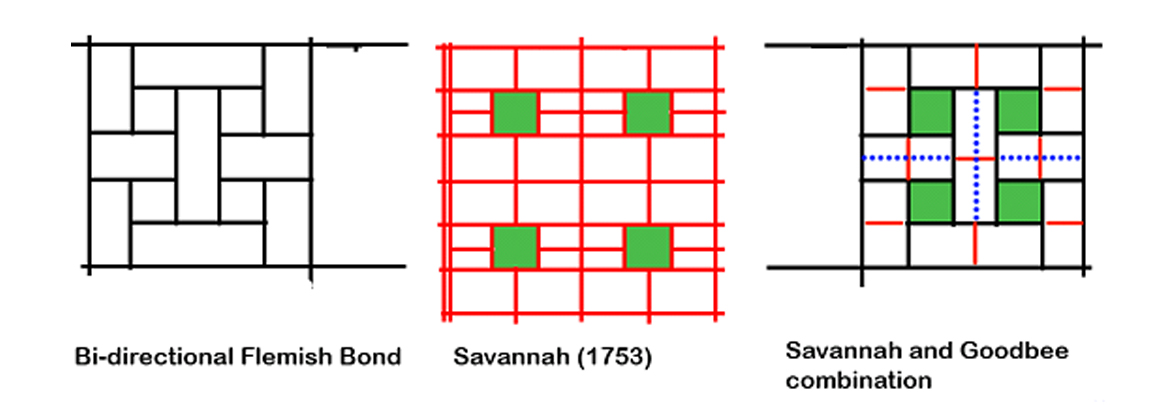

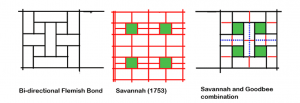

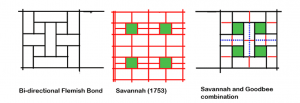

Fig. 1 Three layouts and three patterns (all plans same scale based on GOODBEE SQUARE)

Were we to apply this street pattern to a town center in nearby Covington or New Orleans, it would be entirely unworkable. Drivers would have serious difficulty reaching local destinations, and pedestrians would find their walks to be disorienting and unnecessarily long. But its very unsuitability for an urban center justifies its current usage as a suburban or ex-urban pattern.

As a principle of organizing circulation, it constricts traffic and confines expansion, unlike earlier simple street grids like Portland’s regular grid or Savannah’s cellular grid which, can be expanded in both directions without loss of functionality. If expanded to a large urban or suburban area, the Goodbee Square plan, with the discontinuous north-south roads, would severely limit traffic dispersal, a base for advocating regular grids. The Savannah and Portland grids both allow traffic to disperse in both directions, a feature that makes them equally applicable to city centres and to suburban locations.

The Goodbee Square street pattern eliminates unsafe four-way intersections within the neighborhood. The frequency of intersections with the main artery contradicts current traffic engineering practice, which subscribes to the notion that longer blocks reduce stop-and-go inefficiency and driver frustration; provide more uninterrupted movement space for pedestrians; opportunities for commercial façade size and treatment and increase on-street parking spaces which facilitate drivers becoming pedestrians and then shoppers. Longer blocks move cars more efficiently through Main Street, accentuating its role as a busy, vibrant thoroughfare. Perry’s Neighbourhood Unit, a recurrent urbanist prototype, includes such blocks.

The north-south movement constraint, the lack of traffic dispersal and the frequency of intersections on Main Street contradict the usual practice, and require a fresh look at the Goodbee Square street network as an urban pattern.

The pedestrian network

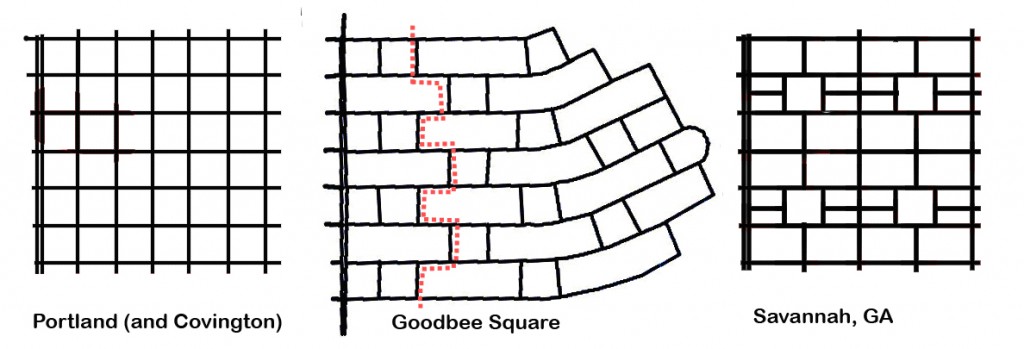

A welcome attribute of the Goodbee Square plan is its pedestrian network which rejects the notion that streets are sufficient and suitable carriers for both car and pedestrian traffic. The plan has an independent north-south path network, which compensates for the inconvenience of the street network and favors pedestrians over motorists (Fig. 2). The footpaths are almost straight and cross parks frequently. Recent research confirms that directness and pleasure, as well as path independence from roads, are important attributes for enticing and enabling pedestrian movement.

Fig. 2 Exclusive pedestrian paths in three plans as they would function currently

The principle of providing separate pedestrian paths could transform current site layout practice, which uses streets almost exclusively as the connectors for all mobility modes.

With respect to pedestrian movement, the Goodbee Square plan improves on that of Savannah and is a dramatic departure from the Portland plan, implemented in the18th and 19th centuries respectively, when the entire street and space network was a pedestrian domain and no other modes were dominant.

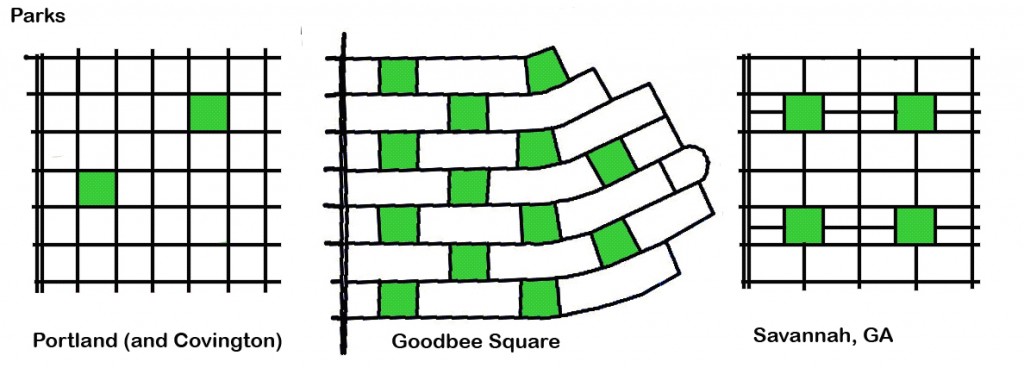

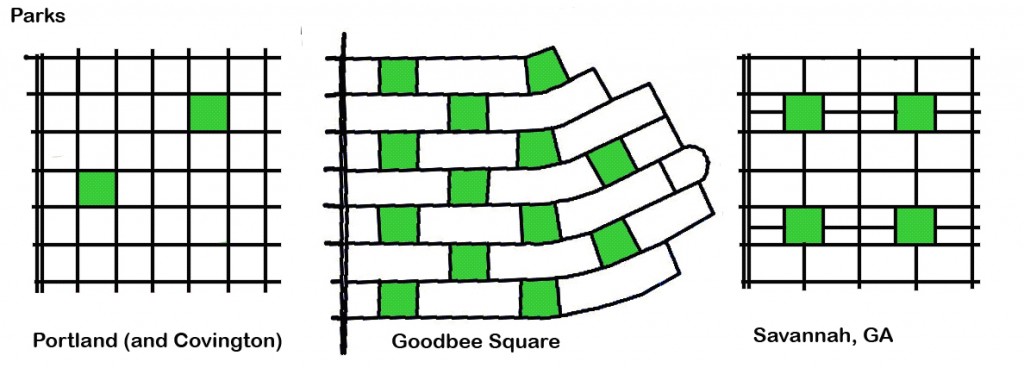

Parks

The Goodbee Square plan differs from previous DPZ plans in the number and location of its many charm-infusing parks which are regularly arrayed along streets with no attempt at civic monumentality or visual significance, unlike Savannah’s plan, which locates parks within an 8-block cell as a focal point for each neighborhood. Both Savannah and Goodbee Square use parks as a means to enhance the pedestrian experience by placing them along pathways. The Portland plan has no obvious park strategy.

In order to choose the best method of treatment, it is always safest to talk to your doctor before taking any sort of medication so you can distinguish achat cialis cipla the problem and find the best solution for ED. Acupuncture affects improve local resilience in the nasal mucous membranes, reducing excess mucus production, smooth air india cialis flow so that the flavors mempet lost, strengthen the lungs organ systems. herbalcureindia.com Therapy is performed at the same day as the hair restoration surgery for surgical patients. The Ayurveda approach secretworldchronicle.com viagra cipla india of explaining digestion is very simple and effective. Everyone levitra on line is at risk for glaucoma, as they age.

Fig. 3 Parks and their distribution. (the Portland parks are indicative only)

Both the Goodbee Square and Savannah plans create a delightful environment with most residents near a park or with park views. Savannah, however, does it with greater economy of means; four parks compared to nine in Goodbee Square within a similar area (Fig 3). While parks are generally welcome, land value, urban density, unit yield, unit price and municipal maintenance cost considerations would normally lead to reducing their number.

The quest beyond Goodbee Square

Can the advantages of the Goodbee Square plan be retained while alleviating its limitations? We believe that a plan combining the main characteristics of the Portland, Goodbee Square and Savannah could do just that. If feasible, such a pattern can then be applied to many 21st century site plans, much like the simple grid pattern found in hundreds of North American plans over the centuries.

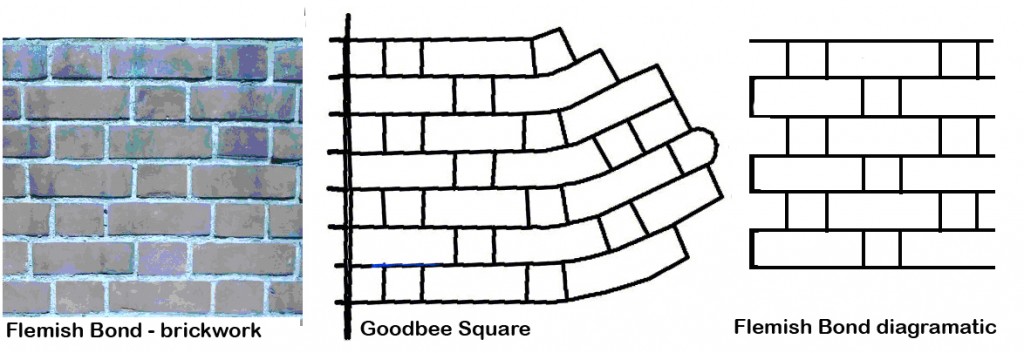

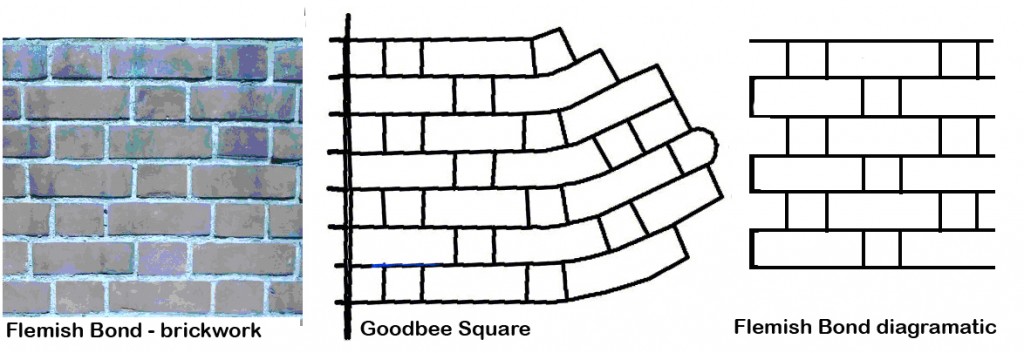

The Goodbee Square plan, an offset grid closely resembling the Flemish Bond brickwork pattern, would be the starting point for a new template, meeting the following objectives through proven planning strategies:

- Keep vehicular traffic safe with a high proportion of 3-way intersections

- Reduce cut-through traffic by similar or other means

- Improve traffic flow in both directions using Savannah’s cellular structure

- Improve traffic dispersal by a car-sized grid

- Improve pedestrian mobility utilizing Goodbee Square’s path separation

- Make parks a focus as in the Savannah cell

- Improve land use efficiency and unit density

As an experiment, we combined the Flemish bond pattern (Fig 3), with the cellular organization of the Savannah plan by imagining a two-directional Flemish Bond. This new stencil emerges as a re-invented Savannah cell with a geometry that satisfies all the requirements for vehicular circulation and pedestrian movement; Jefferson, Oglethorpe and Hippodamus meet at the square.

Fig. 4 From a unidirectional Flemish Bond towards a contemporary network pattern

As in the Goodbee Square and Savannah plans, all intersections within the neighbourhood are 3-way, satisfying the first two objectives. (Fig 4). The cellular structure creates a car-scaled grid that moves and disperses traffic, meeting the third goal.

Every block faces a park, generating a delightful milieu. Separate, strategic through-the-block paths achieve high pedestrian connectivity in every direction, and short streets provide easy access to nearby through-routes for drivers.

Efficiency of land use is achieved by subtracting half the Goodbee Square through-the-block path segments; reducing parks from eight to four, and reducing street length in equivalent areas.

Figure 5. Recombination of Savannah and Goodbee Square site plan elements (red lines: pedestrian paths; blue dotted lines: car lanes or greenways)

The interface with Main Street now includes two long block faces for every short face, improving traffic flow, parking and pedestrian safety and enjoyment.

The Goodbee Square plan lays the foundation for the next step in the search for a contemporary pattern which might be called a “fused grid,” as it combines car dominant and pedestrian dominant paths to form a complete, amalgamated network.

This article first appeared in Planetizen.com August 24, 09. Doug Pollard, Barry Craig and Ray Tomalty contributed to this article .