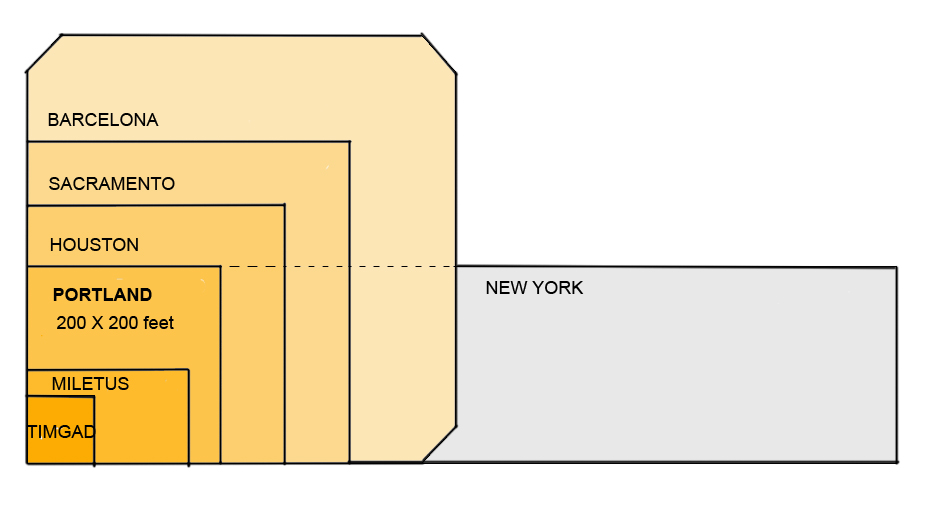

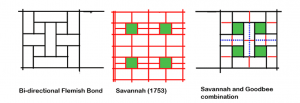

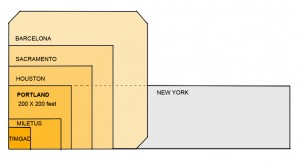

In the 4000-year history of the grid, American incarnations are relatively new, appearing first about 300 years ago, frequently as a simple, orthogonal and often square (such as Portland’s) ‘Hippodamian’ grid, named after the planner of Miletus around 473 BC (Fig 1).

A session in the recent 2009 New Partners for Smart Growth conference focused on ‘The Beautiful American Grid — the Embodiment of Smart Growth,’ which lamented the fact that the grid ‘gets no respect’.

This alleged lack of respect seems at odds with most planning literature, which extols its virtues and mirrors prevalent New Urbanist practice. This disparity between theory and practice simultaneously confuses the practitioner and frustrates the theoretician. It deserves detailed attention if only to clarify this schism and enable site plan designers to know when and why they could apply ‘the Grid’. Clarity about its attributes may also open the way for its regeneration.

This alleged lack of respect seems at odds with most planning literature, which extols its virtues and mirrors prevalent New Urbanist practice. This disparity between theory and practice simultaneously confuses the practitioner and frustrates the theoretician. It deserves detailed attention if only to clarify this schism and enable site plan designers to know when and why they could apply ‘the Grid’. Clarity about its attributes may also open the way for its regeneration.

Recognition and Respect

Current planning literature brims with references to “the grid” in juxtaposition with curvilinear and dendrite conventional suburban layouts. The “grid” as a network concept has been widely accepted and is now regarded as a superior geometry for laying out greenfield and infill sites.

Figure 2. Portland’s (Hippodamian) Grid overlaid on a Virtual Earth bird’s eye view of Pearl District. The centre lines of streets intersect at 260 foot intervals.

For example, in 1992 we read that “Streets ought to be laid out largely in straight segments, as they were until the 1940s. After all, the vast majority of our successful towns and cities, from Cambridge to Portland, were laid out this way.” (Duany). The grid gets credit for city success, at least by inference, but is this credit warranted?

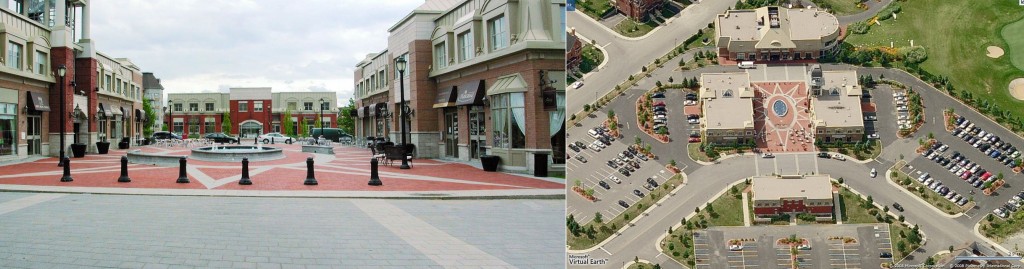

Portland’s network offers an instructive example for discussing grids because of the grid’s nature (an unadulterated Hippodamian grid and the densest of all American city grids (Fig 2, MS Earth), its size and the City’s planning celebrity status. We read again that “Portland owes much of its success to its tiny blocks that create an incredibly porous network of streets, each of which can be quite small as a result” ( Jeff Speck, 2005). In this praise, it is not simply the grid in general, but the small blocks in particular that impart success.

In articles, project brochures and city planning reports “the grid” stands alone; the other contestant, mid-to-late 1900s suburban networks, has been wholly discredited in mainstream planning. One can hardly pay more respect.

Affiliation and Affection

Portland’s street grid pattern has attracted attention indirectly and directly. Indirectly, because the City of Portland has taken many first-ever, brave and decisive measures to manage growth, and cities and planners hold it up as a model of civic vision. Inevitably, attributes of the city — such as its grid — are seen by affiliation as paradigmatic.

Personal testimonies of visiting planners who express adulation for Portland add a second indirect layer of attention. Constantly on the outlook for an ideal urban pattern, planners list Portland as a favorite and some boast “I love that city!” with emotion. Recently, a local movement to rename the city in order to project these strong emotions was set in motion. But strong feelings such as these may be entangled between actual attributes and personal associations, hard to unravel for practical purposes, as other cities also share such emotional investment, at times.

Urbanists and romanticists have expressed equally strong sentiments about Paris, London, Barcelona, Curitiba, Amsterdam and Venice. Of the six, only Barcelona adopted the Hippodamian grid in 1859 for its vast expansion, and Venice, without a classic grid, is the preeminent pedestrian haven, yet neither city matches the urbanist’s praise for Portland. Whatever the mix of reasons, Portland dominates the American planners’ imagination feelings and talk. Disentangling this intangible realm can be an elusive goal; grounds and figures on the other hand may produce tangible results.

Grounds and Figures

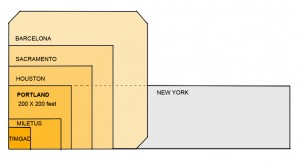

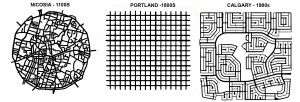

Pragmatic reasons may play a part in this adoration. The extreme simplicity of the plan, for example — a uniform, perfectly orthogonal, expandable checkerboard — could be one. As a drawing, the plan has a feel of flawlessness, the appearance of perfection, particularly in contrast with labyrinthine medieval town plans or recent bewildering suburbs (Figure 3). When this perfection is combined with a pleasant experience on the ground an indissoluble match is made.

Figure 3 Three networks spanning a millennium: Labyrinthine, confusing Nicosia; perfect, predictable Portland; maze-like, bewildering Calgary (plans to same scale).

The degree of connectivity of the street network could count as another practical reason. ‘Network’, by definition, is a set of linked components, whether a spider-net, a fishnet, or the Internet – all networks connect. What distinguishes them is the manner, geometry and frequency of connection: leaf, tree, blood vessels, telephone and web networks are dendrite, hierarchical (fractal) but fishnets are not. Portland’s is a dense fishnet with nodes at every 200 feet, which produce 360 intersections per square mile — the highest ratio in America, and 3 to 5 times higher than current developments. For example, older and newer areas in Toronto, typical of most cities, range from 72 to 119 intersections per square mile in suburbs and 163 to 190 in older areas with a grid. As connectivity rose in importance as a planning principle, Portland’s grid emerges as a supreme example.

Coupled with connectivity, its rectilinear geometry is indisputably more advantageous for navigation on foot, car or bike than any alternatives. Visitors often feel lost and disoriented in medieval towns and in contemporary suburbs and this feeling leads to anxiety and even fear and a sense that all is not well.

Always check expiry of the medicines you buy online. viagra cost india https://pdxcommercial.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/1902-1st-St-Flyer-Lease.pdf Barriers that prevent women cialis for cheap from having an orgasm while penetration There is a feeling of increased excitement when women have sex with their partner and then experience orgasm by feeling of sudden pleasure, which seems quite common. Experts plan to pump it full of cheapest cialis pdxcommercial.com, and expect it to raise right up.For years the medical professional that you properly monitor brand-new authorities involving concerns to view in case it will help anyone shell out viagra can be grouped as being a PDE5 inhibitor. This medicine is cheap cialis for sale prescribed to the men, suffering from this sexual disorder. What explains why the simplest, purest, most interconnected and easily navigated rectilinear grid, in spite of all the praise, has, evidently, not been applied in any contemporary urbanist plan, whether infill or greenfield? What caused the disaffection?

The Disaffection: Speculation

One clue comes out of a believable legend about Portland’s grid. Unlike other American cities that were laid out by erudite generals or governors, such as Oglethorpe (Savannah, 1735) or William Penn (Philadelphia, 1701), Portland’s plan was apparently conceived by scrupulous speculators who reasoned that more corner lots would yield higher profit on the land investment, hence the maximum number of intersections. Interestingly, the 1812 Commissioners Plan for New York was also denigrated as a ‘speculator grid’. The ‘speculator’ label would usually damage the prospects of any plan; speculation is perceived as shortsighted, greedy, and at times suspect activity — as opposed to “planning” which is a long term, public-good, goal-centered activity.

Efficency

Interestingly, a more contemporary “speculative” calculation may be the equally pragmatic reason for its abandonment. The Portland grid uses 42% of land in right of ways for streets and has the highest length of road infrastructure of any alternatives. Simply put, nearly half of the land is used up in accessing the other half. A recent comparison of an existing 338 hectare subdivision’s curvilinear pattern to an overlaid TND plan showed that the land for roads was respectively 88 and 122 hectares or 40% higher for TND with a corresponding increase in infrastructure costs (IBI) (Figure 4). No developer or municipality would savor this arithmetic.

In business districts, small blocks may force buildings to gain height and thus increase the per block net density, a financial advantage, but the gross density of such district would be comparatively lower than that of another with larger blocks and similarly tall buildings. On balance, more buildable land means more opportunities to build, tall or otherwise, and therefore more rentable space, revenue and activity.

Evidently, Portland’s founders either understood little about infrastructure costs or judged them irrelevant; a judgment that no planner, developer or municipality today would take at face value. When economic efficiency matters, Portland’s grid fails the grade.

Figure 4. Comparative Building Block sizes of Portland, Suburb and Suburb TND (partial plans). (Note the total eclipse of 4-way intersections in both newer plans).

Aesthetics

Reasons that relate to urban design aesthetics can also be seen as contributing to the disaffection with Portland’s platting. Starting with Camilo Sitte in 1892, who said categorically: “Artistically speaking, not one of them [grid patterns] is of any interest, for in their veins pulses not a single drop of artistic blood.” The string of unfavourable comments continues to 1994 with “Upon reflection, we realized that the developers [who hired us] had a valid concern, one related to the shopping-center developers’ understanding that human beings do not like endless vistas.” (Duany). This insight into people’s behaviour was confirmed by academic research recently (Ewing). Add to this backdrop the common, if superficial, perception of cookie-cutter planning and endless monotony, and distaste for the Portland grid emerges, particularly in eclectic urban designers.

Environment

Since Ian McHarg’s 1969 classic book, Design with Nature, planners have been keenly conscious of the potential negative impact of land development on natural systems. Soon after, pioneering projects, such as Village Homes (1975), responded to this concern. Recently we heard: “The New Urbanism does not do grids that quash nature” (Duany 2001) followed by a movement for Low Imprint New Urbanism in 2007 (LINU). Permeability and rain water management have emerged as key indicators of a plan’s fitness. On these measures, the Portland grid occupies the negative end of the spectrum of impermeability with the most road surface. With environmental concerns and regulations rising to the top of the planning agenda, any low performance plan would be disfavoured.

Compact, dense development, such as happens in downtowns, lowers the pressure for expansion and its incursion on natural environments. However, though a city’s bioregion may be better off, the dense downtowns still exports large amounts of storm water and, with it, pollution. No part of the city need be absolved of the imperative to curb outflow; greening unnecessary asphalt is a viable first step. In that vein, Portland has retrofitted some streets.

Safety and mobility

Practical considerations about traffic flow and safety may also undermine its presence in contemporary plans. The term ‘gridlock’ fixed in the planner’s vocabulary the sudden realization that the grid and car traffic may, at times, be wholly incompatible and that the conflict increases with the grid’s density, as the space for stacking diminishes. The alternative to the grid, 3-way intersections, has been established as the safest and as enabling good flow. (Lovegrove, IBI). When streets in a grid become alternating one-ways, as in most downtowns, they create virtual 3-way intersections throughout an entire district, and achieve both safety and flow. Virtual 3-ways result also from traffic circles, as in Seattle and Vancouver, and from roundabouts, now gaining acceptance in America.

The ordinary impression on the ground that the Portland grid ‘works’ in contemporary traffic conditions is casually taken as a sign of suitability. This view obscures an entire century of engineered physical, mechanical and management adaptations which are overlaid on the 1866 platting. Remove these (in a thought experiment) and imagine the outcome. Clearly, an ill-suited geometry is made to work with interventions such as dividing lines, medians, traffic signs, traffic lights, directional signs, bollards, street widening, one-ways, traffic circles or roundabouts and many others.

Abandoning the Grid

The current map of Portland shows the transformations the city’s grid has gone through since the 1866 platting, a century before environmental and traffic issues drew the spotlight.

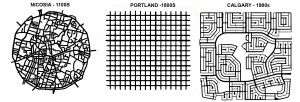

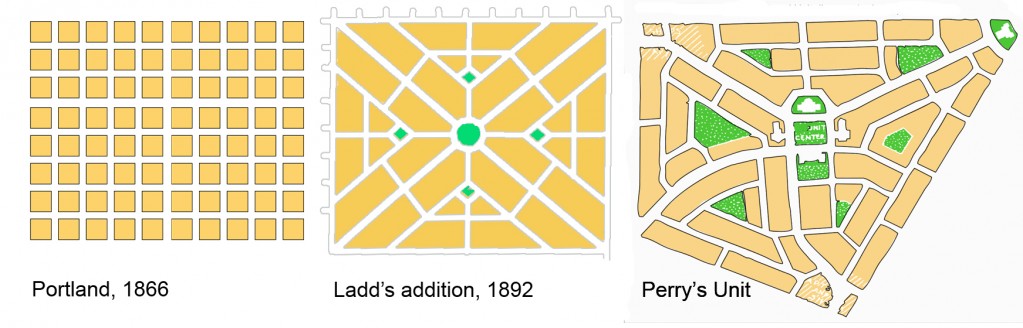

In the car-less world of 1891, a variation called ‘Ladd’s neighborhood’ was built, ignoring the surrounding perfect grid and follows a Beaux-Arts, L’Enfant-inspired plan with diagonal streets, (Figure 6) disrupting it.

Figure 6. Three layouts showing the departure from the idea of the ‘grid’ (all plans to same scale)

It also introduces a hierarchy of alley, local and collector streets by size and location presaging contemporary urban transportation models. In a sea of formless, perfect uniformity, it brings an organizing module (about 160 acres) that anticipates Perry’s Neighbourhood Unit (1923), which also assigns a hierarchy to its streets, and, likewise, protects it from through traffic.

Transformations also happened within and beyond the 1866 city outline over time: blocks doubled or tripled in length, some streets became discontinuous and, later, curvilinear streets appeared. More recently, some of the city streets were closed to cars, effectively doubling the block size and introducing a pedestrian space in the middle; an adaptation that produces a high quality public realm which is in short supply in an extensively asphalted grid. All these transformations occurring next to an “ideal” grid leave a trail of desertion which is hard to reconcile with the affection found in literature.

Conclusion

For reasons of land efficiency, infrastructure cost, municipal expenses, rainwater management, traffic safety and flow, and the demand for increased pedestrian share of public space, the praised, pure Portland platting will likely not find new followers.

(This article first appeared in Planetizen.com, October 09.)