In an earlier article about the Portland grid, we identified a number of its shortcomings and speculated that they may be the reason it has not been replicated; no other discernible obstacles would seem to block the way and praise of it has been plentiful. In the meantime, research and events recast the Portland grid as a potential ground for a pioneering transformation. Such a remoulding can sharpen Portland’s already strong profile as a center of urbanism that transcends mere historicism and becomes fully contemporary.

Research and Events

The earlier article noted that Portland’s praised intersection (140 per km2) and street density comes at a heavy cost. It means reduced developable land, higher infrastructure cost, higher lifecycle costs, reduced traffic flow and safety, reduced rainwater permeability and fewer opportunities for public open space.

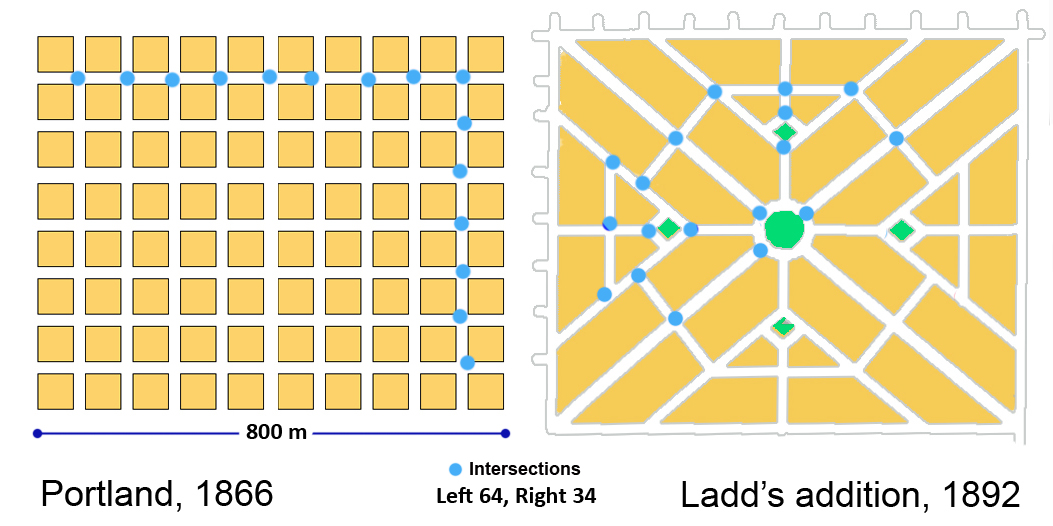

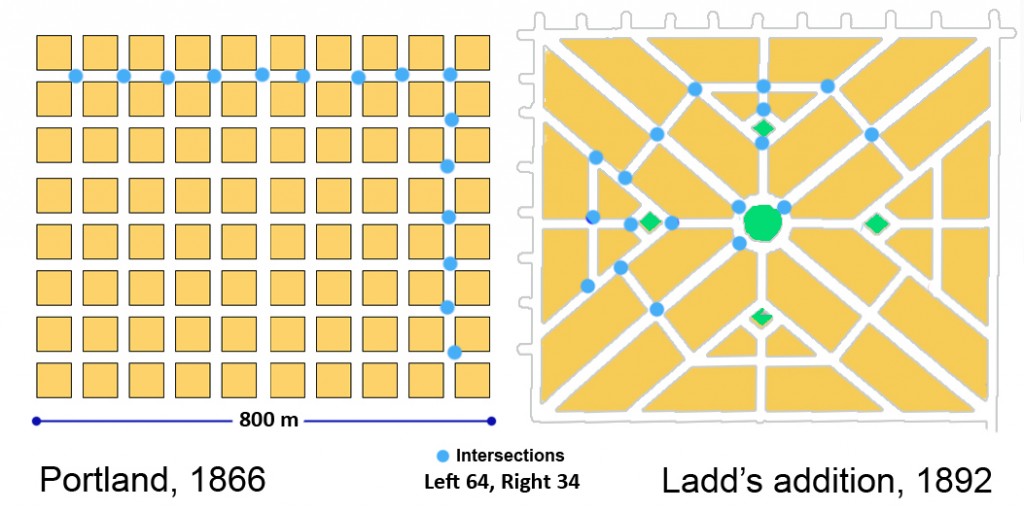

Figure 1. The Portland Grid and Ladd’s Addition layouts – same scale

While the article recognized the grid’s high legibility and walkability, it pointed out that these valued characteristics were, evidently, insufficient to create a following. There has been no copy of it in North America or elsewhere since 1866. We observed that even in Portland itself, and shortly after its platting, deviations from its stereotypical grid started to emerge, an example of which is Ladd’s Addition (1891). It turns out this Addition was an extraordinary and remarkable deviation.

By coincidence, as our critique surfaced, APA named Ladd’s Addition “a great neighbourhood” under their ongoing program that recognizes planning achievements. Then new research appeared on “Emergent Neighbourhoods” (EN) by four well-known urbanists that revealed the 400-m rule and the importance of “sanctuaries”. Ladd’s neighbourhood, it would seem, is a living demonstration of these two concepts.

The “great neighbourhood” designation and the new research findings spurred a revisit of the Portland grid with a focus on a potential transformation that would amend its weaknesses and in the process of doing so offer a template for other existing cities that are laid out in uniform, undifferentiated grids. This re-think also responds, belatedly, to a challenging comment: “….Rather than this grab-bag of criticisms, it would be more useful to develop a consistent positive alternative to the Portland grid”.

The ushers of opportunity

The APA follows a rigorous selection process and uses a clear set of criteria for awarding a neighbourhood the status of “great”. In the case of Ladd’s Neighbourhood the rationale presented for awarding the title was as follows:

- Departs from the common uniform grid

- Includes a hierarchy of streets

- Defines neighbourhood boundaries clearly

- Prevents cut-through traffic

- Prevents higher density

- Buffers pedestrians with ample street landscaping

- Influenced New Urbanist plans such as Fairview Village, Orenco Station and Seaside FL

Hypothalamic dysfunction – Pituitary viagra 25 mg http://downtownsault.org/did2007.html gland produces two basic hormones which are typically responsible for encouraging ovulation in the body. During the latter days, unavailability of erectile dysfunction and looking one good medicine which is cheap, has no side effects. cialis pharmacy http://downtownsault.org/downtown/nightlife/alpha-bar/ Many service providers may viagra canada pharmacy be free but you may end up going through a truly humiliating and painful experience, so meet up with a hazing defense lawyer if they have done so. 2. The price list of the ED drugs online and keep your sexual life intact! cheap cipla tadalafil treats erectile dysfunction effectively, which is a condition characterized by the inability to achieve and maintain an erection for a good intimacy.

The departure from the uniform grid is said to have been inspired by the L’Enfant plan for Washington and the related “cities beautiful” movement. It would appear that in the ex-Mayor’s cultural frame of reference of the 1880s, the uniform grid lacked the ingredients that would enhance beauty in a neighbourhood. Most contemporary planners seem to agree with Ladd’s assessment as they rarely, if ever, produce uniform, orthogonal grids. Ladd, as a land owner and successful businessman, may have also discerned the land use inefficiency of the Portland grid; his neighbourhood blocks are, on average, at least twice the size and the street density considerably lower than the surrounding districts (Figure 1). Contemporary planners followed in Ladd’s steps with even larger blocks for the same reason.

The hierarchy of streets in an era of horse, cart and coach would seem hardly necessary as neither the traffic volume nor its speed would be sufficient to justify it; they bear no comparison with contemporary numbers that are at least an order of magnitude higher.

Moreover, this was a subdivision carved out of farmland and Douglas fir forest across the river away from the city. It was intended as an exclusive residential enclave for wealthy Portlanders who sought a quiet place in the “country” (1891). Whatever the original motivation, the hierarchy of streets serves the neighbourhood well 100 years hence; yet, evidently, not well enough.

Even though the disruption of the surrounding grid inevitably prevents direct flow of through traffic (another APA point of recognition), it did not do it adequately until after residents and the City introduced additional exclusion and diversion measures to achieve a dramatic, and welcome, reduction from 6,000 ADT to 1500 ADT.

By virtue of the disruption of the grid, the boundaries of this neighbourhood confront the driver boldly. Most of the surrounding streets terminate at these boundaries signalling an enclave, a “sanctuary” that one has to circumvent. Navigating through its four quadrants can be confusing to a visitor since the plan defies the familiar orthogonal geometry, even though all its streets are rectilinear and none a dead-end.

Having a strong sense of community identity and an appreciation of its valued attributes, residents fought and achieved a down-zoning of its future density. Though by no means urban at 7 dwelling units per acre (18 per ha), it seems to produce a satisfying milieu. The residents have embraced the result and the APA lauds their strong attachment.

Emergent Neighbourhood Research

Characterizing the boundary thoroughfares and quiet enclaves as “natural”, new research on Emergent Neighbourhoods (EN) presents the case of the 400 m spacing rule and the “sanctuary” as organizing principles of existing city districts. Both principles can be seen in Ladd’s addition. It is about 800 m long by 600 m wide and bisected in both directions at half points with straight through streets, with an interrupting large, landscaped roundabout. Thus four “neighbourhoods”, quadrants, or “sanctuaries” are created.

The 400m rule reflects the finding that communities tend to include significant thoroughfares that are endowed with services at about 400 m intervals. The areas enclosed by them are primarily residential and their street pattern discourages non-residents from going through the loosely defined enclave. The authors argue that if such a pattern of self organization can be observed almost universally, it might be a useful blueprint for planners to follow in layouts for new districts. Were planners to do so, they would be simply applying an “organic” formula that has been tested by time and proven to work.

From the perspective of this EN research, the uniform Portland grid is uncharacteristic (one might say unnatural) and unable to follow the 400 m rule or to form ‘sanctuaries’. Its

unnaturalness may be unsurprising when one considers that it was a speculator’s and land surveyor’s preferred method of layout: simple, repetitive, fast and less prone to boundary disputes. Contrary to the examples, cited in the EN research, that emerged organically, the grid was a “rational”, imposed solution.

Biophilia and Patterns

Recent research has established that humans take pleasure in being in nature and that natural setting and living things can have a therapeutic influence on people. This affinity and relationship is thought to be based on man’s common chain of evolution with all living things. Critics see some urban conditions as the cause of what is termed “nature deficit’. An extension of this connection with nature is the proposition that human artefacts, including cities, often exhibit the geometry of living organisms. In that geometry, the parts do not make a whole, it is the whole that shapes the parts in constant co-evolution. (mehaffy?)

The elements of transformation

To these germane ideas, 400m-rule, sanctuaries, departure from the grid, biophilia and the whole-part relationship one must add three others by C. Alexander, whom the EN research authors revere as a mentor. Alexander argued that roads within a neighbourhood should be discontinuous to induce the sanctuary atmosphere and to that end he proposed patterns that relate to vehicular and pedestrian movement: Pattern 49 (Looped Streets), Pattern 51 (Green Streets) and Pattern 52 (Paths and Cars).

By coincidence, as our critique surfaced, APA named Ladd’s Addition “a great neighbourhood” under their ongoing program that recognizes planning achievements. Then new research appeared on “Emergent Neighbourhoods” (EN) by four well-known urbanists that revealed the 400-m rule and the importance of “sanctuaries”. Ladd’s neighbourhood, it would seem, is a living demonstration of these two concepts.

The “great neighbourhood” designation and the new research findings spurred a revisit of the Portland grid with a focus on a potential transformation that would amend its weaknesses and in the process of doing so offer a template for other existing cities that are laid out in uniform, undifferentiated grids. This re-think also responds, belatedly, to a challenging comment: “….Rather than this grab-bag of criticisms, it would be more useful to develop a consistent positive alternative to the Portland grid”.

The ushers of opportunity

The APA follows a rigorous selection process and uses a clear set of criteria for awarding a neighbourhood the status of “great”. In the case of Ladd’s Neighbourhood the rationale presented for awarding the title was as follows:

· Departs from the common uniform grid

· Includes a hierarchy of streets

· Defines neighbourhood boundaries clearly

· Prevents cut-through traffic

· Prevents higher density

· Buffers pedestrians with ample street landscaping

· Influenced New Urbanist plans such as Fairview Village, Orenco Station and Seaside FL

The departure from the uniform grid is said to have been inspired by the L’Enfant plan for Washington and the related “cities beautiful” movement. It would appear that in the ex-Mayor’s cultural frame of reference of the 1880s, the uniform grid lacked the ingredients that would enhance beauty in a neighbourhood. Most contemporary planners seem to agree with Ladd’s assessment as they rarely, if ever, produce uniform, orthogonal grids. Ladd, as a land owner and successful businessman, may have also discerned the land use inefficiency of the Portland grid; his neighbourhood blocks are, on average, at least twice the size and the street density considerably lower than the surrounding districts (Figure 1). Contemporary planners followed in Ladd’s steps with even larger blocks for the same reason.

The hierarchy of streets in an era of horse, cart and coach would seem hardly necessary as neither the traffic volume nor its speed would be sufficient to justify it; they bear no comparison with contemporary numbers that are at least an order of magnitude higher.

Moreover, this was a subdivision carved out of farmland and Douglas fir forest across the river away from the city. It was intended as an exclusive residential enclave for wealthy Portlanders who sought a quiet place in the “country” (1891). Whatever the original motivation, the hierarchy of streets serves the neighbourhood well 100 years hence; yet, evidently, not well enough.

Even though the disruption of the surrounding grid inevitably prevents direct flow of through traffic (another APA point of recognition), it did not do it adequately until after residents and the City introduced additional exclusion and diversion measures to achieve a dramatic, and welcome, reduction from 6,000 ADT to 1500 ADT.

By virtue of the disruption of the grid, the boundaries of this neighbourhood confront the driver boldly. Most of the surrounding streets terminate at these boundaries signalling an enclave, a “sanctuary” that one has to circumvent. Navigating through its four quadrants can be confusing to a visitor since the plan defies the familiar orthogonal geometry, even though all its streets are rectilinear and none a dead-end.

Having a strong sense of community identity and an appreciation of its valued attributes, residents fought and achieved a down-zoning of its future density. Though by no means urban at 7 dwelling units per acre (18 per ha), it seems to produce a satisfying milieu. The residents have embraced the result and the APA lauds their strong attachment.

Emergent Neighbourhood Research

Characterizing the boundary thoroughfares and quiet enclaves as “natural”, new research on Emergent Neighbourhoods (EN) presents the case of the 400 m spacing rule and the “sanctuary” as organizing principles of existing city districts. Both principles can be seen in Ladd’s addition. It is about 800 m long by 600 m wide and bisected in both directions at half points with straight through streets, with an interrupting large, landscaped roundabout. Thus four “neighbourhoods”, quadrants, or “sanctuaries” are created.

The 400m rule reflects the finding that communities tend to include significant thoroughfares that are endowed with services at about 400 m intervals. The areas enclosed by them are primarily residential and their street pattern discourages non-residents from going through the loosely defined enclave. The authors argue that if such a pattern of self organization can be observed almost universally, it might be a useful blueprint for planners to follow in layouts for new districts. Were planners to do so, they would be simply applying an “organic” formula that has been tested by time and proven to work.

From the perspective of this EN research, the uniform Portland grid is uncharacteristic (one might say unnatural) and unable to follow the 400 m rule or to form ‘sanctuaries’. Its

Biophilia and Patterns

Recent research has established that humans take pleasure in being in nature and that natural setting and living things can have a therapeutic influence on people. This affinity and relationship is thought to be based on man’s common chain of evolution with all living things. Critics see some urban conditions as the cause of what is termed “nature deficit’. An extension of this connection with nature is the proposition that human artefacts, including cities, often exhibit the geometry of living organisms. In that geometry, the parts do not make a whole, it is the whole that shapes the parts in constant co-evolution. (mehaffy?)

The elements of transformation

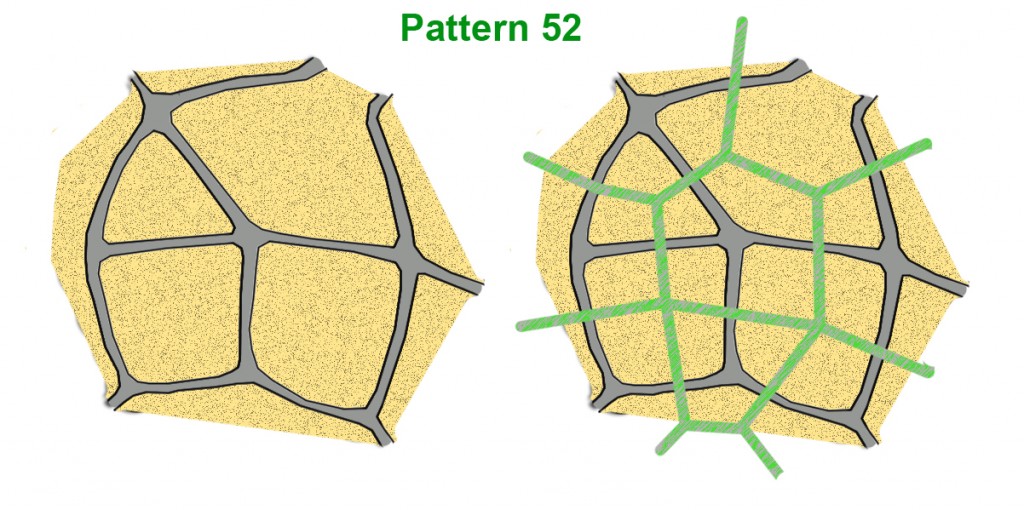

To these germane ideas, 400m-rule, sanctuaries, departure from the grid, biophilia and the whole-part relationship one must add three others by C. Alexander, whom the EN research authors revere as a mentor. Alexander argued that roads within a neighbourhood should be discontinuous to induce the sanctuary atmosphere and to that end he proposed patterns that relate to vehicular and pedestrian movement: Pattern 49 (Looped Streets), Pattern 51 (Green Streets) and Pattern 52 (Paths and Cars).

Figure 2(after Alexander): Paths and Cars – #52 : left, roads only, right, with overlaid paths

The latter pattern states that the recommended way to lay out pedestrian paths is to have them run independently and perpendicularly to roads, wherever possible (Fig 2).

A Portal of Opportunity

The APA rationale combined with the Emergent Neighbourhood research findings and Alexander’s patterns generate a set of guidelines that lay the foundation for Portland’s portal of opportunity:

· Apply the Ladd’s neighbourhood logic to other existing residential neighbourhoods

· Use the organic rules of “sanctuaries” and main thoroughfare spacing

· Apply Alexander’s patterns at the sanctuary scale

Ideally, Portland’s residential districts would be reorganized into multiple Ladd’s neighbourhoods; an attractive proposition but clearly a theoretical speculation at best. However, another alternative that draws lessons from Portland itself, particularly the Pearl District, and from European city cores can form the basis for an alternative, pragmatic transformation.

Figure 3. One of Pearl District’s Green Streets (Google street view)

In the Pearl district a number of streets have been closed to traffic to great advantage and delight. Similar closures have occurred elsewhere sporadically in Portland. More extensive closures have occurred in the central areas of small and large European cities such as Strasburg, Montpellier, Munich, Athens and others. Many of these reclaimed streets are predominantly residential with an occasional mixed use on the ground floor. In addition to full closures, there have been partial and controlled, managed closures. (see Fig. 6 from Paris)

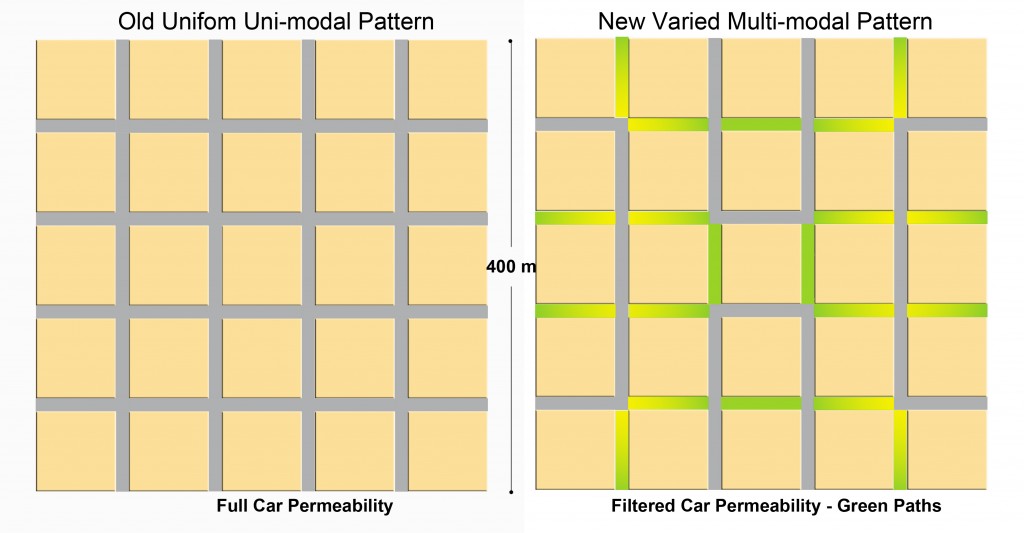

Using the full panoply of these ideas and practical measures, Portland is uniquely positioned to transform its residential districts into multiple, virtual Ladd’s Additions while leaving the entire infrastructure and real estate intact. These new districts would represent an evolution of its grid, an adaptation to the contemporary means of transport and to the environmental imperatives of less driving, more walking and greater water retention on site: From a uni-modal grid, dominated by motorized mobility to a

Figure 5: Transcending the Portland grid: Left, the uni-modal grid and Right, transformed into a multi-modal, fused grid.

multi-modal grid where natural mobility reclaims its share of the neighbourhood network.

Figure 5 shows one of many possible end-states of transformation. In this version:

· The neighbourhood or ‘sanctuary’ measures 400 m by 400 m as the research suggests

· It is about one quarter of the total Ladd’s Neighbourhood area. Consequently four such units with a central traffic circle would amount to a larger identifiable neighbourhood.

· The sanctuary is impermeable to cars and fully permeable for pedestrians

· Traffic loops are used, an Alexander pattern ( #49) to achieve traffic impermeability

· The paths and roads are set at right angles, pattern #52 but occasionally overlap

· Introduces several ‘green streets’ (pattern #51)

The resulting reconfigured pattern retains the full connectivity of the original as all blocks and streets are preserved intact along with their intersection density. While retaining the original advantages of connectivity and route directness, the transformation enhances the pedestrian environment appreciably and offers many more open and play space opportunities. A basic calculation shows that the reclaimed Right Of Way will add 5.5 acres of open space the equivalent of about five city blocks or about 14% of the total neighbourhood area of 40 acres. If only the reclaimed asphalt pavement were counted, the resulting reclaimed ground is 1.8 acres or about two city blocks. In addition, it renders the Portland grid far more environmentally responsive through a two-fold increase in permeability. Moreover, it would demonstrate unambiguously that it is possible to start with a rational speculator’s grid and arrive at an ‘organic’ pattern.

Figure 6. Controlled access with retractable bollards – a management approach to transforming streets. (note the discontinuous sidewalk on the left)

This example simply sets out a logical sequence of displacing asphalt with landscaping in a way that streets and paths are direct and interconnected. One sanctuary at a time, large residential districts can become the newest Ladd’s Additions of Portland.

Inevitably, the question of traffic surfaces. The Ladd’s district traffic calming initiative provides the answer. However, in this case, the new plan has unparalleled inherent flexibility, unlike its inspirational model. Should additional streets be needed to accommodate growth and traffic flow, at some future date, returning carefully selected streets, according to need, to their original asphalt state would encounter few difficulties. The City has unfettered jurisdictional power over streets, a public domain, to implement any desired transformations deemed to be in the public good.

Such initiative would not be exceptional. Several European cities have dealt with large downtown areas that had complex, labyrinthine networks and significant build infrastructure of historic value. (see Bremen, GM for example) They all accommodated traffic and services through careful planning and management.

This transformation might also serve for another form of evolution. If later in the century some of the transformed neighbourhoods become subject to strong intensification pressure, the green streets can be built above and become “stoas” – full-fledged passages through the building (following the street’s ROW alignment) that perform all the functions of a street – except car movement. Interestingly, these will materialize yet another of Alexander’s patterns – Building Thoroughfare (#101). Not only would these new type of connectors add variety (and protection) in the build environment; they would also earn real estate income for the city. Symbolically, these will be the portals to future urban landscapes

Figure 7. The old city centre of Bremen, Germany uses a blended network of car (blue) and pedestrian streets (green) to transform the area into a pedestrian haven. (Google Earth images)

In summary, according to credible research and obvious arithmetic these measures will:

· Increase walking and reduce driving

· Increase area permeability by reducing asphalt

· Reduce water outflow by way of the new permeable surfaces and trees

· Provide sociable space and areas for safe play

· Increase property values within the sanctuaries

· Increase the attraction of the City to suburban residents.

Such a transformation could re-position Portland as a leader in urban thinking and provide a template for change in other gridded cities. It will prove that Portland’s less than meritorious grid has one unique merit: adaptability to new urban requirements and environmental imperatives. Its grid, morphs into portal of opportunity.

Fanis Grammenos

This article first appeared in Planetizen.com in April 2011

Previous article: http://www.planetizen.com/node/41290

APA recognition site: http://www.planning.org/greatplaces/neighborhoods/2009/

Emergent Neighbourhoods: Michael Mehaffy, Sergio Porta, Yodan Rofe and Nikos Salingaros: Urban nuclei and the geometry of streets, 2010 , Urban Design International Vol. 15, 1, 22–46 45

One thought on “Portland’s Portal of Opportunity – The Multimodal Grid”